Authoritarian leaders tend to have thin skins, which is why often the most effective opposition can be political satire, such as Charlie Chaplin’s Great Dictator. But autocrats also lack a sense of perspective, so cartoonists have their hands broken or singers’ vocal chords are cut, as in Bashar al-Assad’s Syria. And sometimes revenge comes in the bureaucratic form of a raid by tax inspectors, as happened recently in India, where Narendra Modi’s government overreacted spectacularly to a measured documentary from the world’s most respected broadcaster.

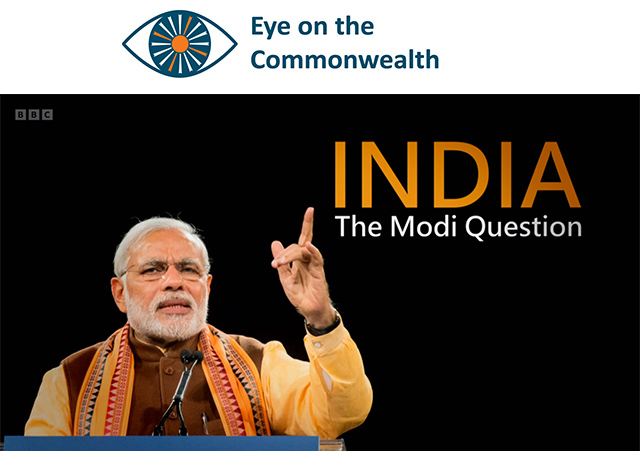

The programme that provoked such outrage, India: The Modi Question, looks at Modi’s background in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a hardline Hindu supremacist organisation affiliated to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and his alleged role while Gujarat’s chief minister in the 2002 anti-Muslim pogrom, in which more than 2,000 people are believed to have been killed. It is not a topic much covered now, as more news outlets shy away from taking on the BJP juggernaut.

Ethnic cleansing

The BBC film quotes a confidential British government report and testimony from a former state minister, Haren Pandya (later murdered), and senior Gujarati police officers in alleging that Modi colluded in ethnic cleansing by creating a ‘culture of impunity’ that allowed Hindu mobs three days to slaughter Muslims before the police were told to impose order.

The documentary also suggests Modi stoked Hindu ‘cow vigilante’ attacks on Muslims, abolished Muslim-majority Kashmir’s autonomy to assert Hindutva ideology, excluded Muslims from the National Register of Citizens, and looked the other way when the 2020 Delhi riots erupted.

Key appointments of the Modi 2.0 cabinet: What they say about Modi’s second term

India braces for radical change under second term of Modi

Transforming the Unbound Elephant to the Lovable Asian Hulk: Why is Modi Leveraging India’s Soft Power?

The government banned the two-part film, using emergency laws under the draconian 2021 IT Rules (described as ‘unconstitutional’ and ‘arbitrary’), as well as blocking links or clips shared on YouTube and Twitter. An information ministry adviser called the documentary ‘hostile propaganda and anti-India garbage’. When students tried to screen it, Jawaharlal Nehru University’s administration cut off electricity to stop them.

‘Tax survey’

During the ‘tax survey’, BBC staff, including five senior editors, were kept there for three nights, with phones and computers seized. A BJP spokesperson called the BBC the ‘most corrupt organisation in the world’, guilty of ‘venomous, shallow and agenda-driven reporting’. The BBC was subsequently accused of tax evasion.

‘Our worst suspicions have been proved absolutely correct: the BBC is funded by China,’ the slavishly pro-government Republic TV (described as more extreme than Fox News) announced, alleging that the documentary was part of a Chinese plot. This absurd claim was based on a Spectator report last year that the BBC had accepted sponsored content from the Chinese company Huawei for its international website, which is funded by ads.

A journalist with Hindutva Watch, which monitors disinformation on Hindu nationalist social media, told the Guardian: ‘These fake allegations are first pushed by rightwing IT cells on Twitter, then they make it on to prime-time television debates and eventually they end up with raids by government agencies.’

Overbroad powers

Amnesty International denounced the raids as an ‘affront’ to free speech, saying: ‘The Indian authorities are clearly trying to harass and intimidate the BBC over its critical coverage of Narendra Modi … The overbroad powers of the Income Tax Department are repeatedly being weaponised to silence dissent.’ The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists said tax investigations were a ‘pretext to target critical news outlets’. The Editors Guild of India noted a ‘trend of using government agencies to intimidate or harass press organisations that are critical of government policies’.

‘Eye on the Commonwealth’ columns look at current issues facing the Commonwealth

A BJP spokesman, Gaurav Bhatia, said the ‘Bhrasht Bhakwaas Corporation’ (corrupt, rubbish, corporation) ‘indulges in anti-India propaganda’, adding: ‘If the BBC did no wrong, then why are [they] scared?’ He also told the opposition Congress party that it ‘should remember former prime minister Indira Gandhi had banned BBC’.

But while the BJP is not the only Indian government to have censored critical journalism, it has taken it to an unparalleled degree, including the widespread use of the colonial-era sedition law. It has also become more unsafe for journalists to do their job: 67 journalists were arrested and nearly 200 physically attacked in 2020, according to a study by the Free Speech Collective. India is ‘sending signals that holding the government accountable is not part of the press’s responsibility. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party has supported campaigns to discourage speech that is “anti-national”, and government-aligned thugs have raided critical journalists’ homes and offices,’ a report by Freedom House said.

‘Blasphemous content’

We live in an age of populist and chauvinist nationalism, as well as rising religious fundamentalism, and the Modi government can point to neighbouring Commonwealth states as examples where free speech is also being stifled. This month, the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority blocked Wikipedia for ‘blasphemous content’. It was part of a ‘concerted effort to exert greater control over content on the internet’, said Usama Khilji, a digital rights activist. ‘The main purpose is to silence any dissent … blasphemy is weaponised.’ Days later a man was dragged out of a police station and lynched by a mob for ‘blasphemy’. It is part of a trend in Pakistan that has seen increasing numbers of liberal academics, atheists, activists and bloggers shut down. One Pakistani commentator said ‘silencing their views so as to not offend the believers is, at best, an antediluvian notion that represses freedoms of belief, conscience and expression’.

Meanwhile, in Bangladesh, Dainik Dinkal, the main opposition party’s newspaper for decades, stopped printing this week after the Press Council upheld a government ban. The move has worsened fears about media freedom there, said Le Monde, as it covered ‘news stories that the mainstream newspapers, most of which are controlled by pro-government businessmen, rarely do. This includes the frequent arrests of BNP [Bangladesh Nationalist Party] activists.’ Reporters Without Borders ranked Bangladesh as 162nd in the world for press freedom – the lowest in the Commonwealth.

‘Electoral autocracy’

But while India is far from alone in trying to gag free speech with red tape, it has perhaps fallen the furthest. In 2020, the Swedish V-Dem Institute’s annual Democracy Report warned that ‘India has continued on a path of steep decline, to the extent it has almost lost its status as a democracy’, due to ‘the dive in press freedom along with increasing repression of civil society in India associated with the current Hindu-nationalist regime’. By 2022, it concluded that Modi had turned India into an ‘electoral autocracy’.

Harassing journalists hardly represents the values that the world’s largest democracy should represent but Modi is not one to let a grudge go. After the Gujarat riots, he was subject to travel bans by Britain and the US that were only lifted in 2012 and 2014 respectively. It was a humiliation for Modi that clearly rankled for years. Now, the brutal details of his alleged collusion in the massacres are being erased or suppressed. History is written by the victors and Modi is quietly editing his own.

Oren Gruenbaum is a member of the Round Table Editorial Board.