Notice from Leicestershire police.

Notice from Leicestershire police.

For an apparently sedate sport, cricket has caused more than its share of international incidents over the years. Australians continued to be incensed at the England captain’s tactics for decades after the ‘Bodyline’ Ashes series in 1932-33 and the Basil d’Oliveira affair in 1967 marked a turning point in apartheid South Africa’s isolation.

But has an international cricket match in the Gulf between south Asia’s arch-rivals ever sparked violent clashes in Europe? This happened after India defeated Pakistan in an Asia Cup match on August 28. Though the game was in Dubai, fighting broke out in east Leicester as hundreds of young men celebrating the victory spilled on to the streets of the city, where 37% of the population is Asian. Local police made 47 arrests and began investigating 158 incidents. ‘Cricket matches between the two teams have long generated large-scale reactions in Leicester,’ the local Mercury newspaper noted.

But, of course, cricket was not really the cause. Though Leicester has been known as a harmonious city of minorities, tensions were rising before the match. In May, a Muslim teenager was allegedly attacked with bats by dozens of Hindu youths, leaving him in hospital (though a BBC investigation cast doubt on whether the incident happened as reported). After the match, celebrating India fans reportedly chanted ‘Pakistan Murdabad’ (‘Death to Pakistan’). Soand Singh, a Sikh butcher, told MailOnline: ‘There’s a long history of people from India and Pakistan living together in Leicester in harmony. We are Sikhs and we don’t have a problem with anybody. But this is scary. This has nothing to do with cricket.’

India at 75: Special edition of the Round Table Journal

India at 75 special edition introduction

India’s Foreign Minister Defends Controversial Citizenship Act

As tensions escalated, Muslims in Leicester filmed mobs of young men marching through streets shouting ‘Jai Shri Ram’ (‘Hail Lord Ram’) – a religious phrase that has recently become synonymous with murderous anti-Muslim pogroms in India. Then someone, presumably Muslim, was filmed pulling down a flag outside a Hindu temple. Videos taken on phones quickly circulated through Hindu and Muslim communities, elsewhere in Britain and abroad.

Inflammatory and often inaccurate social media posts were crucial in stoking the disorder. The city’s mayor told the BBC that the unrest had been fuelled by ‘distorting’ social media, with ‘some of it just completely lying’. One man sentenced over the violence said he had been ‘upset’ by social media. A story seen by countless thousands after being shared by a high-profile Muslim figure was a claim that ‘Indian boys’ had tried to kidnap a Muslim girl, though it was later shown to be fake news.

Even the Indian and Pakistani high commissions spread inaccurate social media. One tweet condemned ‘the violence perpetrated against the Indian community in Leicester and vandalization of premises and symbols of Hindu religion’ – presumably a reference to the flag. The Pakistan high commission denounced ‘the systematic campaign of violence and intimidation that has been unleashed against the Muslims of the area’, despite no evidence of any such campaign.

The Vishva Hindu Parishad (World Council of Hindus), which is aligned with Modi, demanded the British government stop Hindus ‘being terrorised’ and their temples ‘desecrated’ by ‘Islamic extremists’. Meanwhile, the Muslim Council of Britain said events in Leicester were the ‘result of hatred and far-right ideologues left unchallenged, more must now be done to tackle the spread of #Hindutva extremism’. This was a reference to the Hindu nationalist ideology of India’s ruling BJP government under Narendra Modi (whose own rise to power is intertwined with the 2002 Gujarat pogrom, in which at least 1,000 Muslims were killed, when he was chief minister of the state). Leicester’s Federation of Muslim Organisations was more circumspect, warning that the term Hindutva was ‘strictly related to this fascist extreme minority’ and not to ‘demonise an entire community unfairly’.

These posts drew angry young men from elsewhere, both Hindu and Muslim, to Leicester. The Guardian found that half of those arrested were from outside Leicestershire; many travelled from Birmingham, others from London. For Sunny Hundal, in the New Statesman, the incidents were ‘another example of how rising Hindu nationalism in India, which has frequently been directed against religious minorities such as Muslims, Christians and Sikhs, is exporting tensions abroad’.

Is Hindu Nationalism a Threat to Religious Minorities in Eastern India?

The Violence of Security: Hindu Nationalism and the Politics of Representing ‘the Muslim’ as a Danger

Realigning India: Indian foreign policy after the Cold War

BBC Monitoring identified about 500,000 tweets in English about the tensions in Leicester and found that about half came from accounts in India. Moreover, these tweets came from accounts started that month, what it called ‘classic signs [of] “inauthentic activity”, ie a likelihood that individuals are deliberately using multiple accounts to push a narrative.’ It traced many of these tweets back to an Indian news website called OpIndia. A revealing essay in OpIndia describes the events in Leicester as an ‘Islamist rampage’ and condemns Hindu community leaders who stood with imams from the city to appeal for calm and denounce the role Hindutva ideology had played in the disturbances.

For Shoaib Daniyal, the fact that India’s diplomats were weighing in on law and order issues in other countries ‘points to one of the starkest changes that Modi has made while in office: Hindutva is now a major part of India’s foreign policy.’

Oren Gruenbaum is a member of the Round Table Editorial Board.

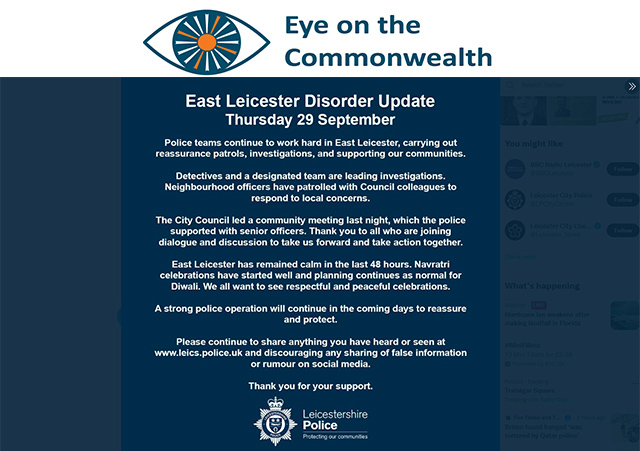

‘Eye on the Commonwealth’ columns look at current issues facing the Commonwealth