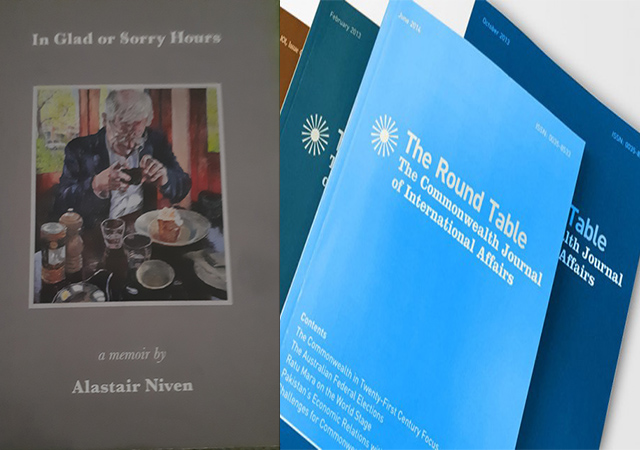

[This is an excerpt from a book review in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

‘According to my mother I should have been the King of Scotland’ is the arresting opening of this engaging memoir. Alastair Niven did not attain royal dignity but he did become a pioneer and founder of the academic study of Commonwealth, especially African, literature and a self-confessed ‘institutional man’ (p. 139), who served in many of the organisations of the Commonwealth and the British and worldwide arts scene. He might be perceived as establishment figure who yet retained a critical and radical edge, a family man with a gift for friendship and as a populariser and proponent of postcolonial literature and ethnic minority arts before and after they became politically correct, a champion of diversity before it was a buzz word.

Niven writes well of a stable childhood and adolescence, neither particularly unhappy nor blissfully happy. His academic record was patchy (maths was a struggle) but he won his place at Cambridge and there, on a board in an unfrequented corner of college, accidentally or providentially, he saw the notice that changed his life. It was an advertisement for Commonwealth scholarships in a number of African countries. He applied in the nick of time and found himself in a state of ‘astonishing ignorance’ (p, 57) (he had not even heard of Chinua Achebe at this stage) on the way to pursue an M.A. in African literature at the University of Ghana. In Ghana he fell in love not only with African literature, culture and cuisine but with his future wife Helen, then a VSO volunteer, later a stalwart of the Open University. This African stint was followed by a PhD at Leeds and teaching at Stirling, the universities pioneering the study of Commonwealth/post-colonial literature in the sixties and seventies.

His next post was as Director of the Africa Centre in Covent Garden in the 1980s overseeing a whirlwind of activities and exhibitions, and one of the best eating places, in Central London, with a cast of colourful and sometimes controversial characters. ‘Much of this endless activity was great fun’ (p. 122). Some of it was ahead of its time including a staged debate on what is now a hot topic of the 2020s, the return of cultural property.

The Commonwealth ‘never well understood in Britain’ (p. 127) was by now, alongside Africa, a major enthusiasm. Chapter 5, ‘Commonwealth, 1980s’, begins with an explanation and a defusing of cynicism

I remain a great supporter of the Commonwealth concept and know from various attachments and links I have had with it over the years that it is a much more practical organisation than most people credit it with being. (p. 128)

In the following decades, Niven visited many Commonwealth countries and there were few Commonwealth networks in which he did not participate. He edited the Journal of Commonwealth Literature, was involved with the international Association of Commonwealth Literature and Language Studies (ACLALS), the Commonwealth Poetry Prize, the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, the Association of Commonwealth Universities, the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize …

The Africa Centre was followed by top posts at the Arts Council and the British Council. These were, it seems, rather less fun and arts funding was always contested. Niven encountered shocking incidents of casual racism and identified a British disease:

I have always believed that Britain suffers from a kind of schizophrenia, its two mind sets perhaps conjoined by avarice. The inventiveness and sense of adventure which built the Empire and created the industrial revolution has always been wrestling with insularity and chauvinism. (p. 172)

There were some controversial decisions and too much crisis management. He was threatened with a court case by Muriel Spark but had many opportunities to promote upcoming young writers in English from the Commonwealth and from British BAME communities. Niven twice served as a Booker Prize judge – a rather unhappy experience in 1994 and a happier one two decades later. He served as President of English PEN. It was a troubled organisation but gave him the chance to campaign of behalf of the Malawian writer, victimised by Hastings Banda, Jack Mapanje whose powerful prison memoir ‘And Crocodiles are Hungry at Night’ began life in the Nivens’ attic.

His last post from 2001 to 2013 was as Principal of Cumberland Lodge, Windsor. Readers who are not acquainted with this national and Commonwealth treasure should refer to its website – https://www.cumberlandlodge.ac.uk/ and they will understand why Niven took such pleasure in the job which ‘brought together all his interests in one place’.

Terry Barringer is the Book Reviews Editor and Assistant Editor of The Round Table journal.

In glad or sorry hours: a memoir by Alastair Niven, London, Starhaven, 2021.