[From the Royal Family website]

[From the Royal Family website]

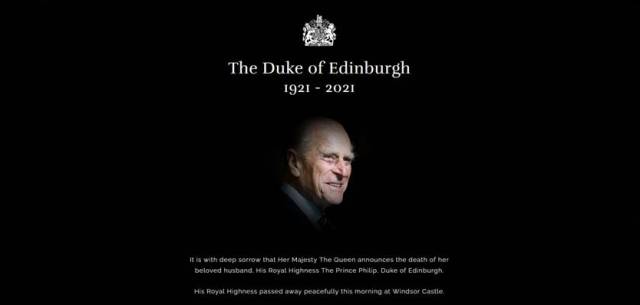

[This article is from a series of regular circulars from Sir Peter Marshall sent to Commonwealth associations. The author has kindly shared this article with the Round Table website ahead of the funeral of Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh.]

“The whole earth is the tomb of heroic men and their story is given not only on stone over their clay but abides everywhere without visible symbol woven into the stuff of other men’s lives”

These sublime words from Pericles’ iconic funeral oration, have a unique Commonwealth resonance on the 17th of April, as Prince Philip of Greece, two millennia later, is buried in Windsor Castle.

When his consortship, unsurpassed in duration and quality, began with marriage in 1947 in Westminster Abbey, he was already a man skilled in the arts of war, and was expecting to continue for a number of years in the exercise of the companion responsibility for keeping the peace after victory had been won.

But it was not to be. Within five years, the untimely death, at the age of only fifty-five, of King George VI, who had spent himself in the service of his peoples in the tempestuous years of war and its exigent aftermath, had placed Princess Elizabeth on the throne at the tender age of twenty-five.

Nor was that all there was to it. In the meantime the King Emperor, manifesting a far-sightedness matched only by its profound sense of responsibility, had welcomed the adoption of an ingenious formula, designed to permit India’s continued membership of the Commonwealth, in spite of its decision to becoming a republic. This transformed him effectively overnight into the (symbolic) Head of the “new” Commonwealth.

Thus to one daunting task – that of upholding and representing the home country in its dire state of exhaustion and impoverishment, and its pervasive problems of adjustment to reduced circumstances – there was added another, namely the esoteric and elusive responsibility of fashioning from our burgeoning association a Commonwealth worthy of the aspirations of the second half of the twentieth century.

Of the outstanding accomplishment of former task, the tale has oft been told. With regard to the latter task, it is said that the British acquired an empire in a fit of absent-mindedness. Be that as it may, there was no room for absent-mindedness in its transformation into the phenomenon we know today. Rather there was unlimited scope for imagination, pragmatism and good will. The upshot was that an association of which the core had once been allegiance to the Crown is now chiefly known for the service unstintingly rendered to it by the Monarch.

This is no case of mere institution-mongering. The phenomenon is a palpable, if not readily definable, force for good. Jahawarlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, famously said that the Commonwealth could “bring a touch of healing to a troubled world”. It has performed that service on more than one occasion in the past. It will certainly do so again in the future.

Prince Philip was a polymath: the range and the depth of his interests and concerns was prodigious. But they can perhaps be grouped together under three rubrics: enhancing the quality of life, especially of young people – notably through the Duke of Edinburgh Awards scheme; protecting, cherishing and safeguarding the environment; and the encouragement and management of change, with an ever vigilant eye to our shared future. Eminently appropriate as these priorities are in the case of those who have responsibility in one country, they are even more suited to the magnificent diversity of the Commonwealth.

What it all meant in practice was described with full understatement by The Queen when reflecting on the role of her husband at the People’s Banquet for their Golden Wedding in 1997: “he has, quite simply, been my strength and stay all these years, and I and his whole family, and this and many other countries, owe him a debt greater than he would ever claim or we shall ever know”. One reviewer summed the situation up with picturesque succinctness: “wit, grit, and irreverence”.

It was another twenty years before Prince Philip retired. There is a strange irony, but also a searching inspiration in that the last year of his life should have on the one hand witnessed so much disruption, distress, suffering and bereavement, to which he was no stranger; and on the other hand so much courage, skill, tenacity and resourcefulness, which were second nature to him.

“I declare before you all” The Queen, as Princess Elizabeth, said in a broadcast from South Africa on April 21,1947, her twenty-first birthday, “that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service”. The consortship began seven months later. You do not need to be an historian to understand its significance in that connexion. Even as we grieve for – and with – Her Majesty and the Royal Family, we look forward to the celebration next year of her Platinum Jubilee, in conditions more normal than those to which we have been variously subjected in the past year.

Sir Peter Marshall is Past President of the Royal Commonwealth Society, a former Deputy Commonwealth Secretary-General (1983-88), a former British diplomat, and a Permanent Representative to the United Nations.

Related articles:

A Remembrance Reflection by Sir Peter Marshall – 2018

A discussion with Sir Peter Marshall – 2017 video

Farewell to John Hall – Peter Marshall