[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

In an era when explicit and vigorous espousal of Christian values by those in public life, especially in Western countries, can prove fatal to their careers, Frank Field has stood out for his courage in swimming against the tide. Seen by many as ‘awkward, unreliable and to some extent a troublemaker’ (p. 2), Field was best known for his 40-year stint as the Labour – and later independent – Member of Parliament for Birkenhead and an indefatigable fighter against poverty and other injustices. But his life and career were notable for two other things, rare among Labour politicians: his passionate belief in the virtues of the market economy and a strong Christian ethos, neither of which he hid from public view.

The latter, we are told, was a particular impetus for this memoir. As Brian and Rachel Griffiths, two close friends who helped with the book, explain in an Introduction,

He wanted to show that his political views and campaigns were derived from and inextricably interwoven with his Christian faith … Living at a time when the Christian faith was in dramatic decline, he recognized that much of his speaking and writing had been to a secular audience, and that in it he had deliberately avoided religious language or Church affiliation. He feared that he might be perceived as a secularist and wanted to make it clear that his political views and actions were founded on the moral values and virtues that derived from his Christian faith. He believe that we could no more invent these fundamental values by human reason alone than that we could invent new primary colours or decide to dispense with the law of gravity. But he also felt that, in public life today, to mention one’s Christian faith risked being thought of as a bit of a crank or, at the very least, as someone who had abandoned their critical faculties. (p. 4)

Field’s Christian values reinforced his growing awareness that rationalism can only take humans up to a point – a lesson he had already imbibed from the philosopher Michael Oakshott. ‘Two crucial aspects of the Christian faith’, he notes ‘ – of the truth being greater than one’s mind can possibly perceive, and that life’s journey is an attempt to move from darkness to light – taught me the limits of rationalism’. (p. 27). That led to him to a feeling of being protected by ‘the gift of a Providential blessing’.

The British Labour Party and the Commonwealth

The British general election democracy and inflation – Democracy and inflation

There are particularly illuminating reflections in the book on the ethics of respect and on the related issue of the collapse of common decencies in the England of today. These reflections are unlikely to endear Field to the metropolitan elite or the chattering classes. Among other things, he provides compelling data on crime which indicate that rising levels of violence against the person are inversely proportional to the state of mutual respect in society: ‘When I was an MP, there were on average more violent crimes against individuals in each parliamentary constituency in England and Wales than there were for the whole country a century ago’. (p. 134) This should alarm any reasonable observer, even after due allowance is made for the growth in the population between the Victorian and Edwardian eras and now.

Field celebrates the success of English Idealism which, he argues, brought individuals and families together and encouraged the belief that ‘each of us should achieve our best self and that society should be so organized that this goal is an effective option for every member of the community’ (p. 143). No less importantly, it promoted the ideal of a virtuous character which is so essential for enlightened citizenship.

He is distressed by what he calls the ‘Balkanization’ of the United Kingdom, and devotes an entire chapter to describing this worrying phenomenon. ‘The most obvious cause for our present discontent’, he laments, ‘is that the writ of the chief forces that shaped the British character no longer runs as it once did. Christianity, Labour’s mutual commonwealth and the public ideology of English Idealism are all but a shadow of their former selves’. (p. 145). Among the manifestations of this development are: widespread yobbish behaviour; the rise of single-parent families; a loss of parental skills; and a collapse of such virtues as politeness, considerateness and thoughtfulness. There is also another factor which, avers Field, cannot be lost sight of:

It is the carelessness, taken to the point of irresponsibility, with which we have not attended to reinvesting in the social capital that underpinned out peaceable kingdom. The country has sleepwalked away from an acknowledgement that the kind of citizenship we had inherited is one which has to be constantly worked out, modified and, above all, renewed. (pp. 151-2)

The book also has much to offer by way of prescriptions to salvage something precious while there is still time, including in the areas of poverty eradication, tackling the scourges of hunger and modern slavery, and enhancing the life chances of children. Field offers chapter and verse on welfare reform – a subject which has occupied much of his political life and which he is still passionate about.

Venkat Iyer is the Editor of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.

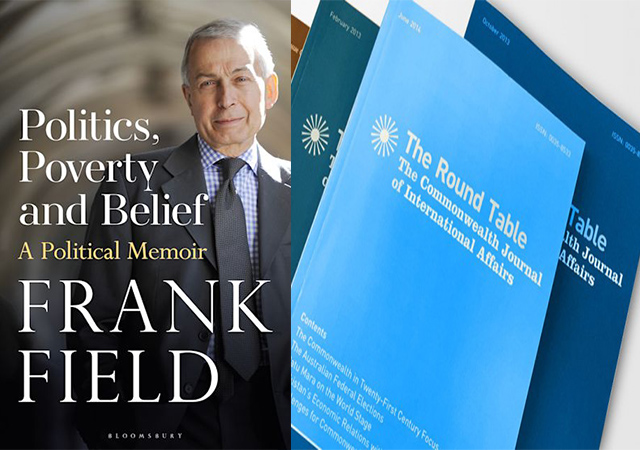

Politics, poverty and belief: a political memoirby Frank Field, London, Published by Bloomsbury Books, 2023.