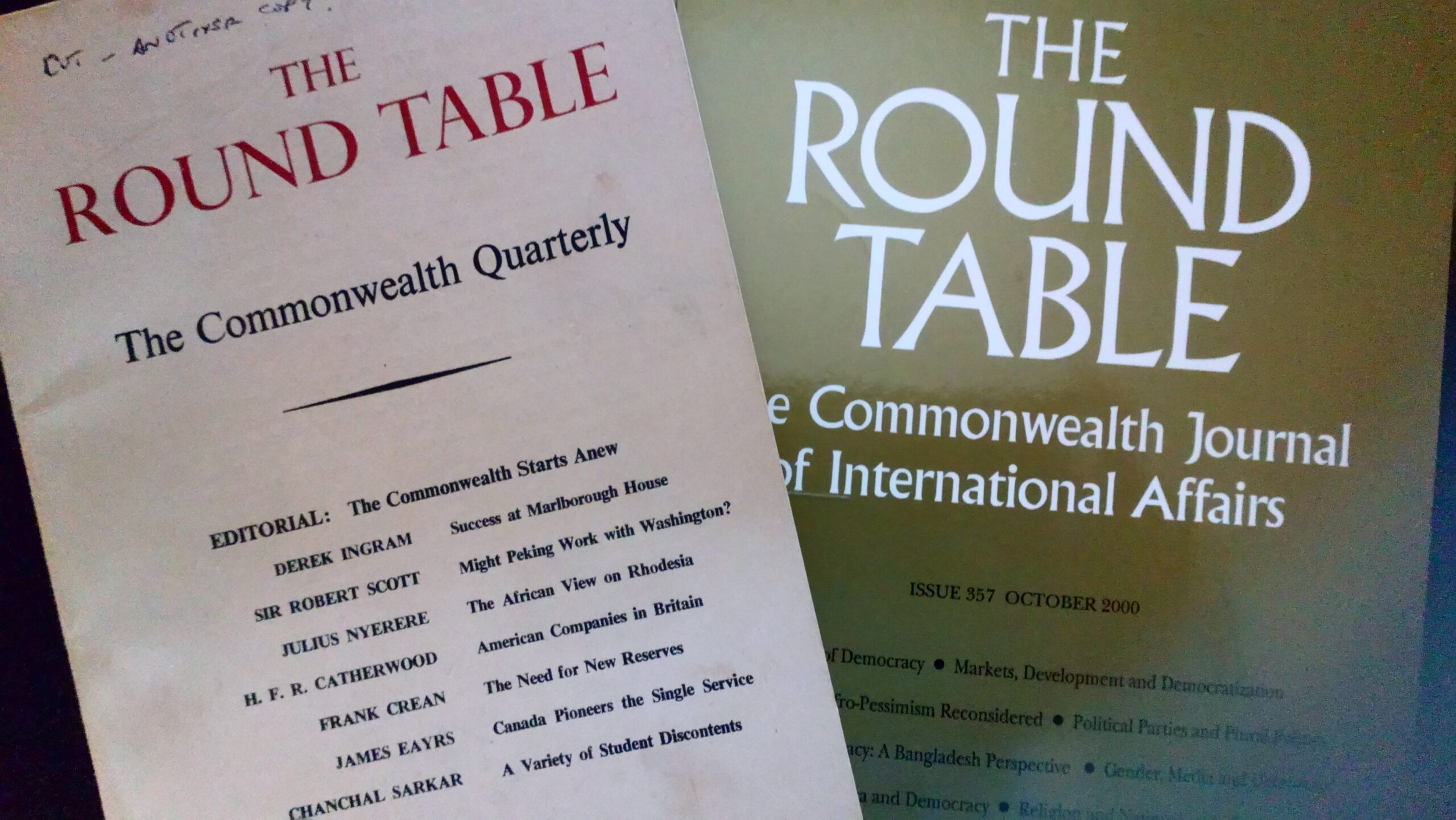

[This 1971 article by Canadian academic Freda Hawkins highlighted the issues around migration at the time. She called for nations to collaborate and view immigration through an international lens. This article is free-to-read under the Round Table’s ‘From the archives’ series until 26 September.]

The study of migration within the Commonwealth commissioned at the Meeting of Commonwealth Heads of Government in London in January1969 was completed by the Secretariat in November. A report was sent to member governments prior to the Singapore Conference and there is a brief reference to it in the Secretary-General’s Third Report to Commonwealth Governments which covers the period from November 1968 to November1970. According to press reports, however, migration was not on the formal agenda of the Singapore Conference, and was not discussed by Heads of Government. It was not mentioned in the final communiqué. Nevertheless, it is believed that this subject, together with the Migration Study was discussed informally at the Conference, and that, as an outcome of these discussions the possibility of further action is now being considered by the Secretariat and member governments. In a sense therefore the future of migration as a Commonwealth concern is in the balance and this is an excellent moment in which to examine and reflect upon this question. Intra-Commonwealth migration must be seen in the wider context of international migration as it is today. The present period in international migration is characterised by a substantial and increasing degree of regulation and control by individual governments. To a considerable extent immigration has come to serve economic development and individual professional opportunity, and the labour market must often be conceived in continental, sub-continental and regional terms. Compared with the large-scale migrations of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, migration movements in the mid-twentieth century have undergone a significant change. Their principal features now include a sizeable professional and managerial component, better-educated immigrants, wider class representation and a more equal sex ratio. The modern immigrant, wherever he comes from, is better informed, more mobile and has more resources to call upon than in the past—resources not necessarily of an economic nature. There is also a fair amount of evidence now from the major receiving countries that the initial sense of commitment among immigrants to a particular country is a good deal less than it was and that return flows may well become larger and circular movements more significant. Planned, short-term migrations are already a major feature of the international scene. But, to an increasing extent, the passport for this kind of travel is skill. It is becoming more and more difficult for the completely unskilled to migrate, and migration as an escape from dire poverty is barely feasible without organized effort and support. The pursuit of skills and talents is world-wide and is likely to involve an increasing number of developed and developing countries. Direct racial discrimination has been giving way in the last few years—very slowly in some parts, but decisively in others—to educational and occupational preference. The brain drain—the increasing migration of professional and skilled manpower to a few affluent, developed countries—has aroused widespread discussion and concern in recent years. It is not a universal phenomenon and does not affect the countries involved in it to an equal degree. Despite considerable interest and continuous investigation, information about its extent and consequences is still very inadequate. Few countries keep satisfactory statistics on migration.

From Empire To Equality?: Migration And The Commonwealth

Empire migration

The migration dilemma

Nevertheless, without any more evidence than we now have, it is plain, that the progressive loss of skills and talents suffered by some developing countries, particularly over the last decade, is a very serious matter. Perhaps even more serious than the loss of trained personnel and specific skills, is the loss of potential political and managerial talent and of men and women of vigour and enterprise, whatever their qualifications maybe. A number of Commonwealth countries are involved in the brain drain, either at the sending or receiving end. Within this general context of migration movements responding to the demands of economic development and technological change in the richer, more developed countries it is essential to remember the very large number of people whose migration from one country to others is involuntary and who desperately need permanent settlement. According to recent figures ,there are now some two and a half million refugees within the mandate of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. But this figure only represents a proportion of the total number now needing assistance, many of whom (like the East African Asians with United Kingdom citizenship)do not come within the official definition of a refugee contained in the1951 Status of Refugees Convention and the 1957 Protocol. A recent estimate from the U.S. State Department suggested that the total number might be as high as seventeen million if all categories of refugees were included. The world’s supply of refugees is also constantly replenished from new sources. In 1970, over half the U.N.H.C.R.’s total programme budget of $5.76 million was earmarked for Africa where there were known to be some 900,000 refugees in need of assistance.

Problems of International Migration

If international migration today is largely a jungle very little or subject to any kind of order, at least it can be said that some individual manage migration very much better than they did; that in general the lot of the immigrant and, in many countries, of migrant labour is much improved; that migration within the European Economic Community has been, on the whole, a very successful enterprise for all concerned; and that, since the Second World War, a considerable international effort has been made for refugees, although any permanent solution of this problem is unlikely. One should also mention among the forces working for order (in relation to permanent settlement), U.N.H.C.R., itself, the Inter-Governmental Committee for European Migration (I.C.E.M.), and the international voluntary agencies who work valiantly in this field. Perhaps ” jungle ” is too strong a word? But, as an image, it may convey the extent to which many aspects of international migration resemble impenetrable undergrowths into which no one has ventured. More research is urgently needed. This is an area of serious academic neglect, although demographers, sociologists and, to a lesser extent, economists have taken an increasing interest in it in recent years.