David Cameron urged to take five steps towards tackling corruption and rooting out hidden money [credit: UKGov website]

David Cameron urged to take five steps towards tackling corruption and rooting out hidden money [credit: UKGov website]

An unusual bus tour was driving around the more exclusive districts of London in early May—not homes of the stars, as in Hollywood, but homes of the corrupt. The Kleptocracy Tour, the Singapore Straits Times reported, was set up by Roman Borisovich, a Russian campaigner against corruption, to highlight the leading role of the UK capital’s property market as a destination for dirty money and the teams of British intermediaries, such as banks and law firms, which make it happen. ‘The idea behind the tour is to attract public attention to the fact of massive money-laundering through properties in London,’ Borisovich said.

More than 36,000 properties in London are owned through offshore firms, which in total own £122bn ($175bn) worth of property across England and Wales. Buying properties through offshore companies can be used to hide the true owners and avoid paying taxes.

As the ICIJ made clear, there are legitimate uses for offshore companies and trusts, and there is no implication that any persons or companies in the Offshore Leaks Database have broken the law or otherwise acted improperly. However, the ICIJ’s scoop has put London’s perpetually overheated property market under intense scrutiny.

One of the stops on the Kleptocracy Tour is a six-bedroom house with an indoor pool on a private road near Hampstead Heath in north London. It used to belong to James Ibori, ex-governor of Nigeria’s oil-rich Delta state, who received a 13-year prison sentence for money-laundering and fraud in 2012. The house cost £2.2m, yet his governor’s salary was £4,000 a year. The Metropolitan police estimated that Ibori embezzled $250m of Nigerian public funds, the Guardian reported.

Commonwealth member states but especially the UK’s Overseas Territories and Crown dependencies dominate the list of tax havens used by Mossack Fonseca: the British Virgin Islands account for half of all the companies it incorporated, followed by Anguilla, Bahamas, Jersey, Niue, Seychelles, the UK, Belize, Cyprus, Isle of Man, Malta, New Zealand, Samoa and Singapore.

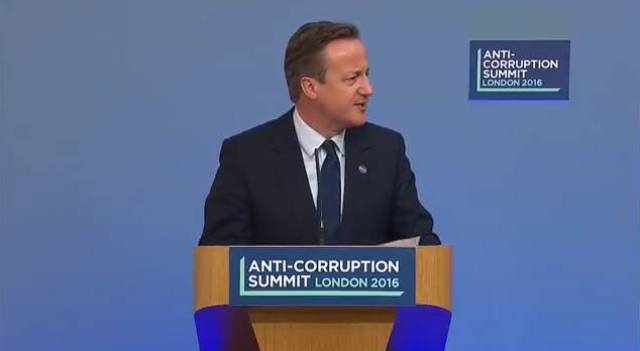

In the wake of the release of the Panama Papers, the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, hosted an international summit on combating corruption, pushing to end the secrecy that hides most of the offshore market. The Guardian, which helped publish the Panama Papers, suggested five steps Cameron could take to clean up the sordid mess: create registers showing beneficial owners of companies to show who really profits from them; make the registers public; impose direct rule on the overseas territories if the tax havens do not co-operate; make publishing detailed accounts mandatory; and ban fake ‘nominee’ directors.