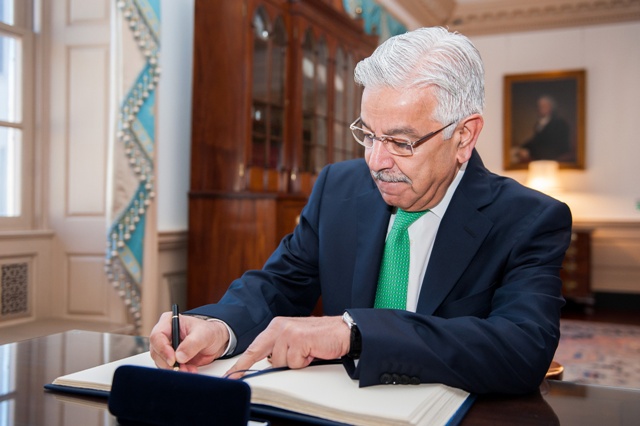

Pakistani Foreign Minister Khawaja Muhammad Asif signs US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson's guestbook before their meeting at the US State Department in October, 2017. [State Department Photo]

Pakistani Foreign Minister Khawaja Muhammad Asif signs US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson's guestbook before their meeting at the US State Department in October, 2017. [State Department Photo]

Donald Trump saw in the new year as he left the old one, tweeting petulantly in the early hours. The first country the US president decided to pick a fight with was Pakistan – keystone of US foreign policy in south Asia since Henry Kissinger recognised its strategic importance in the late 1960s. In his first tweet of 2018, Trump said: ‘The United States has foolishly given Pakistan more than 33 billion dollars in aid over the last 15 years, and they have given us nothing but lies & deceit, thinking of our leaders as fools. They give safe haven to the terrorists we hunt in Afghanistan, with little help. No more!’

As so often with Trump’s incendiary texts to the world, the president’s aides were left scrambling to repair the damage. The next day Pakistan summoned the US ambassador, David Hale, to explain his president’s declaration. The US State Department then declared it was suspending security assistance, although the Guardian suggested: ‘The vague details suggested the primary goal was to substantiate Donald Trump’s surprising New Year’s Day tweet.’ Pakistan accused the US of treating it like ‘whipping boy’ and said Washington was no ally. Khawaja Asif, Pakistan’s foreign minister, called the US ‘a friend who always betrays’.

Trouble had been brewing since August, when the US, which has provided more than $33bn in aid over the past 16 years, warned Islamabad that it was withholding $255m until Pakistan became more willing to crack down on militant jihadists. The New York Times reported that the Pakistani military’s refusal to hand over a member of the Haqqani network captured when a US hostage was freed had widened the rift between the allies. The Haqqanis, who once claimed to command a force of more than 10,000 fighters, were a favourite mujahideen group of the CIA and Pakistan’s ISI when they were killing Soviet soldiers in the 1980s Afghan war but had become enemy terrorists when they began attacking US forces in Afghanistan.

Washington, infuriated that Islamabad allows the Haqqanis a base in the Waziristan tribal areas to attack US and Nato forces over the border, has been pressing the ISI and the military to cut the militants loose for years. But, as the US found when its own carefully nurtured jihadi allies turned on it after the Russians left, Pakistan fears what may happen if it tried to kill off the Haqqani network, which is already believed to support the Pakistani Taliban. In an article at ETH Zurich’s Centre for Security Studies, a former Pakistani general, Talat Masood, is quoted in 2011 predicting that sooner or later Islamabad would have to choose between its useful, if wayward, regional proxy and its American paymasters. ‘If Pakistani gives the indication that it’s very stubborn and obstinate and will not change its policy and will continue to do what it is doing at the moment, then, I am afraid, it will have to choose between the Haqqani group and not only the US but the western world.’

“Terrifying without American money”

But, writing in Foreign Policy, Christine Fair of Georgetown University argued that Pakistan would ultimately ride out the storm, shrugging off the latest censure from Washington because it was just too important to alienate. ‘There is little that is, or ever will be, new in Trump’s Pakistan policy [for] two simple reasons: the logistics of staying the course in Afghanistan and the night terrors triggered by imagining how terrifying Pakistan could be without American money.’ Foremost among these nightmares, Fair says, is US fears of what might happen if Pakistan lost control of its many nuclear warheads – which are perhaps increasing by 20 a year, the Washington Post reported. With Pakistan’s record of trafficking nuclear secrets, its relaxed attitude to transporting them (in ordinary vans, the Atlantic claimed), and what Fair calls ‘a petting zoo of every kind of domestic, regional, and transnational Islamist terrorist organisation thriving under [Pakistan’s] protection’, it seems a reasonable concern. Secondly, she says, if the Trump administration was serious about applying financial pressure it would let the International Monetary Fund cut off the financial tap to Islamabad. However, with the nuclear threat looming in the background, she adds: ‘Pakistan has essentially developed its bargaining power by threatening its own demise.’ And, she says, the US has put itself in an impossible position in its ‘unwinnable’ Afghan war: reliant on Pakistan’s air and land corridors to move supplies, rather than working with the far less dangerous Iran. ‘Logistics will beat strategy every time.’

Ayesha Siddiqa, at Soas University of London, concurs, telling the Guardian: ‘Ultimately, the US will have to come to the table. It’s an issue of logistics. The American military understands this and the Pakistan military understands this too.’ Pakistan, she said, ‘will soften a bit, there will be some negotiations, some concessions will be extracted, and maybe somebody from the Haqqani network will be shot dead. But I don’t see any major change in policy.’