[This book review appears in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

Rule by self-serving dynasties and military dictators or religious zealots rarely leads to stable government and a prosperous country. Combine all three and the result is almost inevitably negative. That has been the plight of Pakistan since it was created in 1947, split in two with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, and then faced with the additional burden of becoming a buffer state on the edge of communism after the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, leading to years of turmoil and terrorism.

Two new books trace aspects of this history through the prism of the Bhutto family, which has provided two prime ministers – Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and his daughter Benazir – plus her husband Asif Zardari who became a surprisingly resilient president after her assassination. Benazir’s and Zardari’s son Bilawal is now limbering up uncertainly as the head of the family’s Peoples’ Party of Pakistan (PPP), awaiting his turn, if the military is willing.

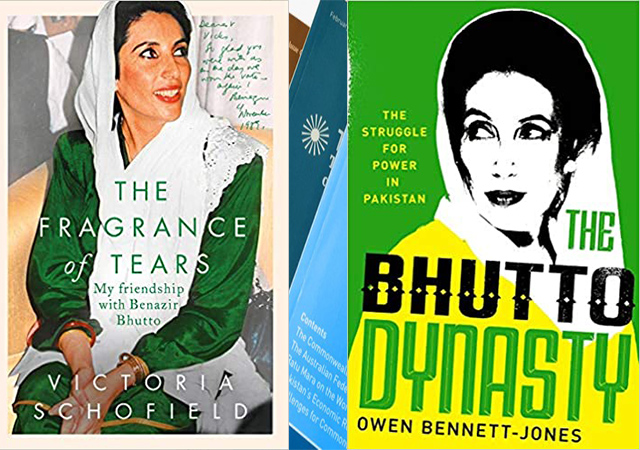

One of the books is by Victoria Schofield, an historian and author, who has produced a carefully crafted personal memoir of her 33-year long friendship with Benazir (like both authors, I am using first names for the Bhuttos). This is a delicately painted human story of a friend who became prime minister twice between 1988 and 1996 but is often seen as one of the more disappointing South Asia dynasts.

The other book is by a former BBC journalist, Owen Bennett-Jones, who has specialised in Pakistan for many years. He has produced a well-researched and detailed biography of the dynasty, written with a reporter’s eye for detail.

He originally planned a book on Benazir after producing a series of BBC podcasts on her assassination in 2007. He then expanded the scope to cover the dynasty, including Zulfikar and their ancestors, tracing the family’s origins back twelve centuries to Hindu Rajput (warrior caste) origins when their name was probably Bhutta or Boota. An ‘a’ at the end of a family name often became ‘o’, we are told, ‘as part of the process of colonial anglicisation’.

It is easy to take a negative view on Benazir, even though she was regarded in the west as something of a heroine. She can be seen as a spoilt and occasionally fierce-tempered feudal autocrat, with a dynast’s strong sense of entitlement, who fell too easily in with the corrupt ways of Zardari after their arranged marriage and failed to turn the advantages of her upbringing, including five years at Harvard and three at Oxford University, into a positive force for change when she became prime minister.

Schofield opens up a more personally sympathetic view in her memoir that gently tracks Benazir’s life from Oxford University to Pakistan at the time of Zulfikar’s trial and hanging in 1979, then into active politics, marriage, periods of house-arrest and exile, prime ministership, and an eventual triumphant final return from exile to re-enter active politics – and assassination a few weeks later. Throughout, Schofield was involved to varying degrees as friend, assistant, letter-writer, lobbyist, companion at important events, and family confidante and guardian.

The relationship begins at Oxford University in 1974 when Schofield arrives as a fresh undergraduate and is introduced to Benazir, who invites her to ‘come and have tea’. Those are the ‘salad days’, recounted in a chapter laced with a social calendar of amply annotated notable names, both women becoming presidents of the Oxford Union.

Later, in May 1978, Schofield receives a letter from Benazir that she says changed her life, leading to a concern for Pakistan, and also Kashmir, that continues today. It was an invitation to visit Pakistan just after Zulfikar had been condemned to death for alleged murder. Schofield goes, presumably for a few weeks, but stays for nearly a year, broken only by a brief Christmas visit home.

She joins the team defending Zulfikar, typing and carrying briefs including his own submissions and letters to world leaders, and she becomes a companion for Pinkie, as Benazir was known to her friends. This is the most interesting part of the book because Schofield is there, in Pakistan, sharing the hopes, the worries and despair, developing friends and contacts and occasionally writing for The Spectator.

Back in the UK, she joined the BBC and wrote a book of her experiences, Bhutto: Trial and Execution, that was published by Cassell. It was, she readily admits, greeted as ‘biased’. Tariq Ali said she was ‘a chum so made no attempt to objectivity’. (Oddly, Bennett-Jones makes no mention of Schofield or her book.)

In later years, Benazir is frequently living a distant life from her friend. But the relationship becomes so close that, when Schofield offers to help with the Bhutto children after Benazir’s assassination, Zardari says, ‘Yes of course you must stay in touch with them. You know they smell her on you’.

Schofield brings her subject to life with so much insight that one longs for a little less discretion and a few more personal revelations and discussions on policy. Her story, spanning 33 years, is remarkable. It must be rare for an outsider to draw so close to a top politician and national leader and not only sustain but develop the relationship over a long period without being drawn into the political maelstrom – and without any attempt to cash in on the closeness, even though Schofield clearly enjoys the contacts and experiences.

Bennett-Jones fills in a lot of the details and both books tell us that Benazir roared around Oxford in a yellow sports car, an MG. Schofield however is silent on her much-gossiped relationships, and Bennett-Jones provides just two words – she ‘dated men’.

It would have also been interesting to hear more from Schofield about the steps that took Benazir to an arranged marriage at the age of 31 when she was back in Pakistan. I was spending a lot of time there for the Financial Times at the time and know (from one of them) that she cast her eye over three or four possible husbands before allowing her family to find a candidate.

In many ways Zardari, who came from a feudal Sindhi family and was known around Karachi as a fun loving, party-going polo player, was a disaster. The Bhuttos apparently thought he’d be harmless, never foreseeing how he would lead the couple into charges of massive corruption. He was labelled ‘Mr Ten Per Cent’ because of his alleged take on investment projects, for which he was jailed.

Benazir seems to have been content with the match and Bennett-Jones tells us that ‘he delivered for her’. He quotes a US ambassador who said (while discussing how she had tried to justify their corruption) that ‘she was completely in love with him; she could never deny him anything’. Benazir however told Hilary Clinton at the time of Bill Clinton’s Lewinsky scandal that ‘We both know from our own lives that men can behave like alley cats’. Sadly, Schofield is silent on such things. Also it would have been useful to know from Schofield about how she saw Benazir’s successes and failings, and the hopes for Bilawal – her book ends in 2008.

Bennett-Jones lists the negatives on her rule, quoting a veteran bureaucrat who said she allowed the ‘destroying of financial institutions, rampant corruption, loot and plunder, widespread lawlessness, political vindictiveness and senseless confrontation with the senior judiciary and the president’. Others said she was too pro-American (she certainly had friends and supporters there) and was insufficiently committed, early on, to Pakistan’s nuclear programme.

Her father’s biographer said she was too focussed on glorifying Zulfikar’s memory and not enough on helping the poor. On the nuclear issue, Bennett Jones analyses and does not dismiss a report that Benazir took nuclear secrets in an overcoat pocket on a trip to North Korea – it is known that that the countries shared know-how, but the overcoat story is contested.

Bennett-Jones gives Zulfikar credit for managing political realities and shepherding Pakistan’s 1973 constitution through parliament, but criticises him for not dealing strongly enough with the temporarily weakened military and for curtailing individual freedoms, and ailing critics. On Benazir, he praises her personal bravery that continued to her death, but criticises that she ‘never managed to assert her authority over the Pakistani state as a whole’ and became too arrogantly assertive about the dynasty.

Looking back over those years, it is a story of missed opportunities. Perhaps the greatest was that Benazir and Rajiv Gandhi, then the Indian prime minister, did not survive for long enough to try to bridge the gap between their two countries. Both books mention how they first met soon after Benazir became prime minister at the end of 1988 and had hopes that they could leave the past behind and move ahead. But it was not to be – neither country’s establishments wanted the youngsters’ enthusiasm (Rajiv was 44 and Benazir 35) to become policy. And it never has.

John Elliott is a member of the Round Table Editorial Board.