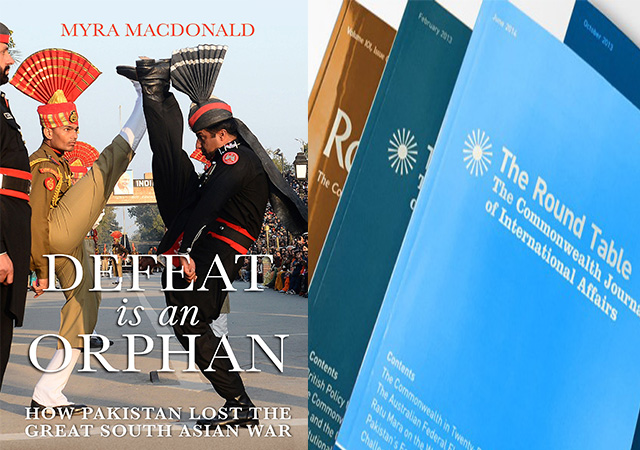

Chair of the Round Table’s Editorial Board Victoria Schofield reviews the book Defeat Is an Orphan: How Pakistan Lost the Great South Asian War for the Round Table Journal’s Book Reviews section.

Excerpts below are from this review.

In this forthright account, as the subtitle suggests, Myra MacDonald explains why Pakistan has lost what she describes as the ‘Great South Asian War’ against neighbouring India, making the country an ‘orphan’ while India has achieved a victory ‘that has many fathers’. Having been assigned to India in 2000 as Bureau Chief of Reuters, her book is the product of ‘many years of engagement’ with both India and Pakistan, as evidenced by her sources and acknowledgements. MacDonald’s timeline of study covers the years between 1999 which marked a low point in the Indo-Pakistani relationship following the Kargil war to the present day…..

Integral to MacDonald’s narrative is the history of the disputed state of Jammu and Kashmir as well as the ambivalent relationship between Pakistan and Afghanistan at a time when Afghanistan was in chaos and crisis. Following Musharraf’s failed peace mission to India in 2001, the attacks on the Srinagar legislative assembly and Parliament House in New Delhi, once more brought the countries close to war. Both armies massed along the international border and foreigners were encouraged by their respective governments to leave. Although on this occasion the war was averted, it was a salutary lesson for Pakistan: so convinced were the Indian soldiers that they had mobilised in order to advance into Pakistani Punjab that they were disappointed when they had to pull back. But the tension between the two countries was only reduced not eradicated. Again paradoxically, it was Musharraf who presided over an improvement in relations when, for the first time since 1947, the line of control was officially opened in 2005 to enable regulated intra-state movement to take place. Domestic compulsions, however, within both India and Pakistan contrived to stall any further agreements.

Then came Benazir Bhutto’s assassination in December 2007 and the succession of her husband as President of Pakistan in place of Musharraf, who had irrevocably lost ground domestically by coming into countrywide confrontation with Pakistan’s lawyers. Any prospect of picking up the pieces of the previous administration’s peace initiatives was lost by the Mumbai terrorist attack in November 2008. Although the Indian reaction was less robust militarily than that in 2002, and despite protestations of innocence at government level, Pakistan was once more portrayed as the instigator.

These events took place nearly a decade ago, but the mistrust and hostility between the two countries has remained, fuelled by continuing minor confrontations and terrorist attacks. The Jammu and Kashmir issue lingers on as a painful reminder of India and Pakistan’s opposing viewpoints and mutual failure to come to terms with the de facto situation as opposed to the de iure one. Even in this era of post-modernism which claims that truth is a construct developed and maintained by power through structuring discourse, it is hard to contradict Myra MacDonald’s thesis. While India is striding into the 21st century as a promising regional power, Pakistan appears to be side-lined. An uncertain variable, however, is the beneficial impact of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). While MacDonald is right in claiming that China has had ‘no patience’ with Pakistan’s ‘risk-taking’ (p. 240) against India, the new boost to their economic relationship may leave Pakistan as less of an orphan than her narrative suggests, although Pakistanis will have to contend with a strong streak of Chinese paternal interest.

Unfortunate as MacDonald’s analysis may be for those who would like to believe that Pakistan is the victim of a succession of international conspiracies, India should also not be portrayed as an innocent player in their failed relationship. The genuine casualties of the longstanding enmity between the two neighbours are their respective societies, whose members have had to endure the political, social and economic consequences of seventy years of hostility, especially those living in Jammu and Kashmir.