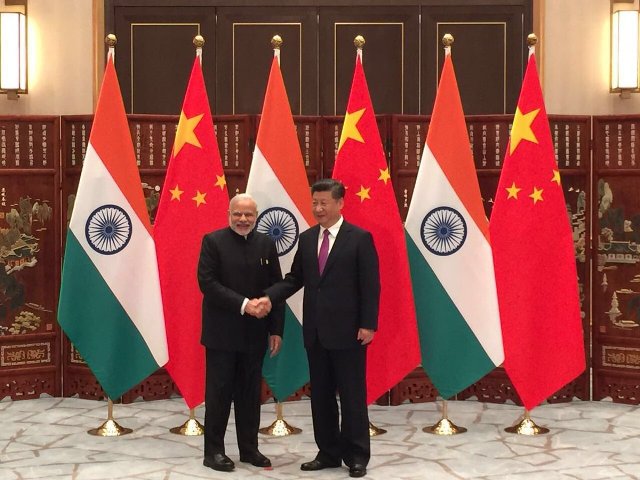

Prime Minister Modi meeting during his 2016 China visit with Chinese President Xi Jinping. [picture: Prime Minister Modi on Twitter]

Prime Minister Modi meeting during his 2016 China visit with Chinese President Xi Jinping. [picture: Prime Minister Modi on Twitter]

[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs]

China is India’s biggest neighbour and we need to understand the Indo-Chinese relationship from several angles and aspects. Both countries have serious problems to resolve, such as the border, water-sharing, regional cooperation, etc., but given their respective sizes and potential they are also countries which can define the future destiny and direction of Asia and the world beyond.

India–China relations have been complicated and interesting. The current relations have stabilised somewhat since the border skirmishes at Doklam in 2017. The relationship is strengthened due to close mutual engagement at various forums like the Wuhan summit, Mamallapuram summit, BRICS summit, etc. Such bilateral meet-ups do have positive effects.

The India–China partnership

There are four constituents in the multidimensional India–China partnership. The avenues for economic co-operation between the two countries are still wide open. China is keen in investing in Indian markets especially building infrastructure and fifth-generation technology architecture. India on the other hand wants greater access to Chinese markets due to its yawning trade deficit. Of the about $84 billion bilateral trade, India and China are also committed, following agreements at the highest political levels, to not only co-operate on bilateral issues but also in regional and international affairs. For example, at the Wuhan summit both countries agreed to work in tandem in Afghanistan.

At the same time, China in 2013 announced a major strategic programme to create its own geo-strategic cosmos known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This was done without consultation with India. To make matters worse, shortly thereafter a China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) was bought under the rubric of the BRI. The CPEC involves a serious violation of India’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and has been rejected.

Secondly, India and China are pillars of an emerging world order. In addition to the trade and economic partnership that has evolved since the beginning of this century, the two countries have also entered into a large number of agreements ranging from agriculture to diary, education, science and technology, and climate change. The potential for co-operation against terrorism is substantial but China consistently holds back due to its support for Pakistan. Regrettably, the frequently expressed intentions to diversify and deepen the relationship notwithstanding, movement on the ground remains inadequate, in spite of the potential and the opportunities.

India’s place in America’s world under the Biden presidency: decoding the China factor

COVID-19 and India’s withering pandemic diplomacy

Multilateralism in South Asia during the COVID-19 pandemic: an Indian perspective

Thirdly, China has shown an ambiguous stance in relation to Pakistan. For example, it has soft-pedalled on the declaration of Masood Azhar as an international terrorist and on the grey-listing of Pakistan by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

The unpleasant fact of this diplomatic landscape is the power imbalance between the two Asian giants. China’s aggregate GDP is now a staggering $14 trillion which is nearly five times that of India at $3.8 trillion. China has also outpaced India in the much needed modernisation of its armed forces and better defence organisation. China does not co-operate with India on shared river water resources. Its unflinching and blind support for Pakistan, including in the military and nuclear matters, shows that China is only using Pakistan as a pawn against India. It interferes in South Asia and in the Indian Ocean region to compete with India’s interests. It also makes threatening moves on its borders with India from time to time. This calls for India to work on maritime security and be vigilant of actions within its neighbourhood on a sustained basis.

Yashvi Barot is at St Xavier’s College, Bombay, India.

Related articles and opportunities:

Student event: Decolonising the university and its curriculum: the challenge for the Commonwealth

Routledge/Round Table Commonwealth Studentship Awards

News and informed opinion from The Round Table

Find out more about The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs