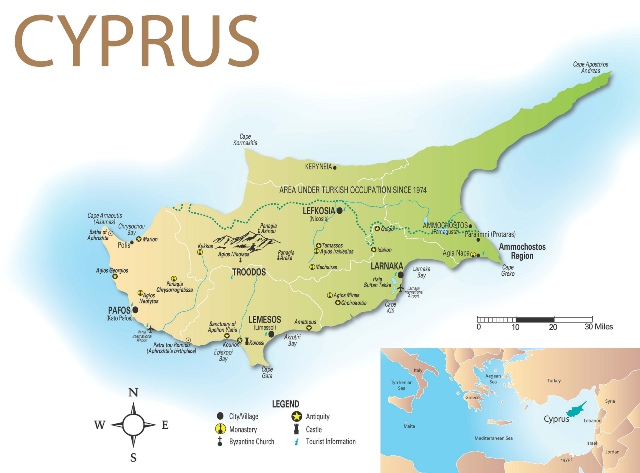

Last chance for a deal? 'Cyprus is called the ‘graveyard of diplomats’ for good reason' [map from CTO Zurich]

Last chance for a deal? 'Cyprus is called the ‘graveyard of diplomats’ for good reason' [map from CTO Zurich]

In 1954, speaking about Cyprus, Harry Hopkinson, Britain’s minister of state for colonial affairs, told MPs: ‘There are certain territories in the Commonwealth which, owing to their particular circumstances, can never expect to be fully independent.’ To that bald declaration could now perhaps be added: ‘And certain divided territories can never expect to be reunited.’

The latest attempt at brokering a peace deal on the island has, like before, apparently reached an impasse despite hopes that this time things might be different. The talks are seen by many as the last chance of permanently ending the 1974 partition of Cyprus, when Turkish troops invaded after a Greek Cypriot coup – led by the national guard and backed by the military junta in Athens – intent on enosis (union with Greece) ousted the Cypriot leader, President Makarios. Urging both sides to take risks for peace at the talks in Switzerland, the European Commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, said: “Without over-dramatising what is happening in Geneva, this is the very last chance to see [a solution for] the island being imposed in a normal way.”

Cyprus is called the ‘graveyard of diplomats’ for good reason. Even Henry Kissinger, all-powerful US secretary of state and national security adviser to Richard Nixon, had to admit he had failed to deal adequately with this conflict between two Nato allies (though many analysts would say he bore much responsibility for it, and did so even at the time, according to the New York Times in 1974). Time has compounded the problems. About 18% of the population was Turkish Cypriot at independence in 1960 but the invasion created 200,000 refugees (about 165,000 of them Greek Cypriots), and after years of settlers from Turkey arriving, the number of Turkish Cypriots has now more than doubled so their share of the total population now corresponds to the 38% of the island occupied by Turkish troops in 1974. Large-scale population exchanges are possible but unlikely, though a transfer did happen in 1975. Also vital to forging peace is the unresolved fate of those who disappeared in 1974. The Committee on Missing Persons is excavating mass graves to discover the fate of the 1,600 to 2,000 missing islanders, presumed killed in revenge attacks by both sides. Returning remains to grieving families helps heal old wounds.

Remaining divided

But attempts to end partition have a sad air of inevitability about them. In the six decades since independence in 1960, the island has remained as much of a geopolitical prize as it was for ancient empires. It was a tug of war between nationalist regimes in Greece and Turkey, a pawn in Cold War machinations by the Americans and Russians, and remains an uncomfortable reminder of the colonial past (3% of the island is still held by Britain as military enclaves – the ‘Sovereign Base Areas’ of Akrotiri and Dhekelia). Another source of tension lies in the Greek part of the island being part of the European Union, and enjoying the prosperity this has brought, while the north remains isolated, with talks on Turkey’s accession to the EU stalled as long as the unrecognised Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) exists. Ironically, far from adding to this combustible mix, age-old religious differences between Muslim and Christian communities are not a major source of friction, with the local heads of the Orthodox Christian, Armenian, Maronite and Roman Catholic churches as well as the Turkish Cypriot grand mufti all supporting the peace process.

In 1989, the Cypriot president, George Vassiliou, began talks under Boutros Boutros-Ghali, UN secretary-general. Boutros-Ghali’s proposals were accepted by Vassiliou but rejected by the Turkish Cypriot leader, Rauf Denktash, in 1993. Further talks mediated by the UN envoy Gustave Feissel failed too. Negotiations resumed in Troutbeck, New York, in 1997, ending with no result but warmer relations. However, a further round in Montreux the same year made no progress.

A UN security council resolution in 1999 led Kofi Annan, UN secretary-general, to persevere through five revisions of plans for a federated republic but a referendum in 2004 saw the proposals accepted by Turkish Cypriots but rejected by Greek Cypriots, largely over the right of return to land lost in 1974. There was another attempt to restart talks in 2008, when the Cypriot president, Demetris Christofias, met the Turkish Cypriot leader, Mehmet Ali Talat, who had supported the 2004 plan. Talks resumed again in 2014 but foundered on the recent discovery of large gas deposits in Cypriot territorial waters (the extent of which was itself contested). ‘Instead of galvanising the feuding communities to conciliate, the prospect of finding alternative energy supplies appears to have widened the gulf between them,’ the Guardian noted. Hopes rose again with the election of a left-wing moderate, Mustafa Akıncı, as Turkish Cypriot prime minister in April 2015. While he wisely played down expectations, a sense of cautious optimism grew.

Talks focus

The talks focus on six areas: governance, economy, EU affairs, property, territory and security. Many issues at stake have remained constant since the 1970s, such as security guarantees and the right of return for displaced islanders, but others are newer. Ankara wants rights acquired through EU membership, the acquis communautaire (especially the ‘four freedoms’ – free movement of people, goods, services and capital), to be extended to Turkish Cypriots, or all Turks, after any deal, despite Turkey being outside the EU. But, the Cyprus Mail reported, Juncker said Turkey’s demand was not a bilateral issue but concerned all of the EU and could not be accepted under any circumstances.

Governance has been a sticking point that bedevilled previous talks but this was neatly addressed in 2014 when the then Turkish Cypriot leader, Derviş Eroğlu, and the Greek Cypriot leader, Nicos Anastasiades, issued a joint declaration at the start of the latest initiative, stating: ‘The settlement will be based on a bi-communal, bi-zonal federation with political equality. [It] shall have a single international legal personality and a single sovereignty … There will be a single united Cyprus citizenship … All citizens of the united Cyprus shall also be citizens of either the Greek-Cypriot constituent state or the Turkish-Cypriot constituent state.’

The TRNC’s economic problems are plentiful, largely stemming from the embargoes that block agricultural exports, stymie tourism and push up the price of imports through Turkey. Its trade deficit is huge: exports of $130m a year against imports of $1.4bn. As Mustafa Besim, an economist at Famagusta’s Eastern Mediterranean University, notes, it is an aid-dependent economy, with Ankara directly providing 30% of the TRNC’s budget and financing infrastructure. The PRIO Cyprus Centre thinktank valued the peace dividend at €20bn over 20 years with a growth rate three times higher than under the status quo. Clearly, Turkey has a huge incentive to find a peace deal. The economic problems of Cyprus, despite EU membership, are also profound, stemming from its role as an offshore haven. In 2013 it needed a €17bn EU-led bailout and many of its banks were revealed to be conduits for money-laundering by the Russian mafia, (as covered in Commonwealth Update).

Another problem is the issue of properties abandoned in 1974. Is compensation sufficient or is restitution required? The return of Morphou, a town in rich citrus-producing land, is a red line for many Greek Cypriots, the Cyprus Mail reported. Turkish Cypriots, prepared to give it up in 2004 under the Annan plan, are now refusing, stalling talks in November. In January, both sides rejected maps showing proposed borders, AFP reported. Even compensation is problematic. In 1998 the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg ordered Ankara to pay a Greek Cypriot woman for the loss of property in Kyrenia. Turkey paid up five years later but did not comply with another ECHR ruling that she could reclaim her property. In 2014 the ECHR ordered Turkey to pay €90m to Cyprus for the invasion but Turkey’s foreign minister then, Ahmet Davutoğlu, called the judgment ‘neither binding nor of any value’.

Security

Security is another hurdle, with Turkish Cypriots fearful of Turkey’s 30,000 troops withdrawing but Greek Cypriots adamant that an ‘occupying force’ must go. Turkey, as one of the three guarantors of the Zurich and London agreements in 1959 with the UK and Greece, refused to relinquish that role but the Greek president, Prokopis Pavlopoulos, said in November: ‘The institutional hierarchy obviously excludes a confederate solution or occupation armies and obsolete guarantees, which deprive the modern concept of sovereignty of its meaning.’ However, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the Turkish president, said in January that a full pullout would be possible if Greece, which also deploys a small force in Cyprus, did the same. According to Parikiaki, the new European parliament president, Antonio Tajani, ‘believes the EU itself could act as a safeguard for both the solution’s viability and the security of Cypriot people in their entirety.’ Encouragingly, the UN envoy brokering these talks, Espen Barth Eide, said at a US Atlantic Council forum in March: ‘Security and guarantees will not be the thing that locks this conference.’ But Eide does see other roadblocks on the way to a deal, telling the Greek Cypriot newspaper Politis and the Turkish Cypriot Kibri that gas finds (France‘s Total and Italy‘s Eni are to begin drilling off Cyprus in 2017) and poor relations between Greece and Turkey were obstacles. ‘A few years ago it was considered there was no hope. But now we have support from the security council and the EU. All these still exist, but I see the first signs of fatigue,’ he said.

To the frustration of those trying to end one of Europe’s longest-running conflicts, a symbolic gesture by one side can destroy at a stroke much of the goodwill built up in patient talks. One such event came in February, when a small group of nationalist Greek Cypriot MPs voted to introduce an annual commemoration in schools of the referendum in 1950 in which 96% of Greek Cypriots voted for enosis. The fact that this inflammatory move was passed by just 19 votes, thanks to the ruling Disy party abstaining, exasperated both the main opposition Akel party, Turkish Cypriot leaders, the Turkish government and Anastasiades, who is head of Disy. According to the Cyprus Mail, Anastasiades admitted: ‘Yes, I believe [the decision] was wrong, not only as regards timing but also as regards its goal.’ However, he also claimed the Turkish Cypriots had used the gesture as a pretext to pull out of talks. For Turkey’s prime minister, Binali Yıldırım, the vote suggested ‘Greek Cypriots were never sincere from the beginning’. He told the Turkish daily Hürriyet: ‘You hold talks about everything but right after that they legislate for the commemoration of enosis every year … That destroys everything that has been said [in talks].’ Noting that previous Turkish Cypriot leaders had referred to enosis in slogans to suggest Greek Cypriots had never given up on the idea, Eide said: ‘This is a real problem when the one side, in the most delicate moment, involuntarily or voluntarily invokes an issue that touches on the fundamental fears of the other community.’ However, Erdogan is not above invoking irredentist notions himself, recently bemoaning the loss of Aegean islands to Greece under the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, the pact that defined modern Turkey’s borders following the collapse of the Ottoman empire, Kathimerini reported. Leaks have also fuelled mistrust. After documents emerged in January revealing major differences on governance, property, right of return, work permits for Turkish Cypriots, public-sector jobs and the timetable, the Greek Cypriots said they would no longer distribute documents at the Geneva talks, the Guardian reported.

Erdogan’s role

But perhaps the greatest threat to a deal is the increasingly autocratic Erdogan himself. In an article entitled the ‘Sultan of An Illusionary Ottoman Empire‘, New York University’s Prof Alon Ben-Meir said: ‘A quote attributed to him in 1999 describes precisely what his real intentions were from the day he rose to power. “Democracy” he said, “is like a bus, when you arrive at your destination, you step off.”’ Erdoğan has been accused of stalling the peace talks until a constitutional referendum in April on radically extending the powers of the Turkish presidency has passed – trading co-operation in Cyprus for support from Turkish nationalists to strengthen his position at home. Anastasiades accused Akıncı of delaying negotiations to avoid overlapping with the referendum, Reuters reported. Speaking to Kathimerini, Anastasiades said: ‘I hope this is just a bid to strengthen or galvanise Turkey’s domestic front so Erdoğan can achieve his objectives.’

A resolution of the Cyprus question was always a prerequisite for Turkey’s accession to the EU, but Erdoğan, for so long pursuing membership, has cooled on the idea, hinting at a referendum on whether to pursue talks. His angry war of words in March with the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, and the Dutch (calling both governments ‘Nazis’) and threatening to pull the plug on an agreement to stem the flow of migrants to Europe, have not helped his cause, even if the rhetoric is largely for domestic consumption. Erdoğan was ‘looking for “imagined” foreign enemies to boost his nationalist base in the run-up to the referendum,’ said Soner Çağaptay, at the Washington Institute.

The Economist takes a sceptical view of the likely outcome of the peace talks, not least because divisions have become so entrenched (it points out that 48% of Greek Cypriot students have never visited the north). It also sees the security guarantees as a major problem, quoting Anastasiades’s remark that: ‘It was like asking Latvia to accept a Russian security guarantee.’ The newspaper concludes: ‘To bet on a reunified Cyprus implies a faith in Mr Erdoğan’s statesmanship that the president has done little to warrant.’ In January 2016 the Eurasia Group consultancy put the chances of a breakthrough agreement at 60%, Global Sources reported. ‘The real risks to the success of a reunification deal will follow this breakthrough on property and territory, and will be largely in the hands of external actors,” it noted. ‘Turkey must come out in support of a deal that no longer features its right to unilaterally and militarily intervene on the island, and international actors will also have to commit to economic support to make reunification viable … considerable risks remain.’

Despite Erdoğan, there has been undoubted progress at the talks. But are there underlying factors that militate against an end to partition? The refusal of the British government in 1954 to contemplate self-government was largely due to the priority given to ‘stable conditions in this vital strategic area’, as Hopkinson put it. This was two years before the Suez crisis doomed Britain’s imperial pretensions and Cyprus was crucial to safeguarding the approach to the Suez canal, and as a military and air base in the Levantine Mediterranean. As Brendan O’Malley and Ian Craig noted in their book, The Cyprus Conspiracy, by 1974 the Cold War was warming up and Cyprus was by now crucial for electronic surveillance of Soviet nuclear missile tests and to protect the vulnerable eastern flank of Nato.

Makarios

Archbishop Makarios was that rare thing, an able and wily head of state with the added authority of being a spiritual leader. ‘Suspicious of Western intentions, Makarios reinforced his strategy of relying on world opinion – and particularly the influence of non-aligned countries, to safeguard Cyprus’ sovereignty,” the Washington Post said. The British had exiled him to the Seychelles in the 1950s and he survived several assassination attempts and the Greek colonels’ coup attempt. As Makarios had worked successfully with the Cypriot Communist Party, the Americans saw him as the ‘Castro of the Mediterranean‘.

O’Malley and Craig argue that for Kissinger (James Callaghan, then British foreign secretary, had to acquiesce to US policy) the interests of Cyprus were expendable faced with what they saw as a maverick leader, who had already appealed to Moscow to protect his country’s independence, about to lurch to the left. ‘As we made clear in British Guiana, we are not prepared to tolerate the establishment of Communist regimes in British colonies,’ Hopkinson told MPs in 1954.

A BBC documentary in 2006 quoted George Ball, the acting US secretary of state, telling a former British intelligence officer in the 1960s: ‘You’ve got it all wrong, hasn’t anyone told you that our plan here is for partition?’ The scholar Constantine Danopoulos has also argued that the Greek military regime saw partition as satisfying the aims of Washington and Nato to resolve the festering sore of the Cyprus problem while also achieving the goal of enosis.

O’Malley and Craig’s book makes a strong case for the argument that, long before the invasion, the US and UK already saw ‘double enosis’ – permanent division of the island between Greece and Turkey – as the best way out of a labyrinthine diplomatic crisis. A declassified CIA briefing from 1964 supports that conclusion. The geopolitical tectonic plates have shifted but interests have not. Now, 43 years on, it may be too late for Cyprus to bridge the fissures left by the invasion. As the latest peace talks appears to be running into the sand, it seems likely that partition is here to stay.

[Oren Gruenbaum is the Editor of Commonwealth Update. The Update appears in full on the Round Table Journal website.]