[Photos: Hansard and New Zealand National Library].

[Photos: Hansard and New Zealand National Library].

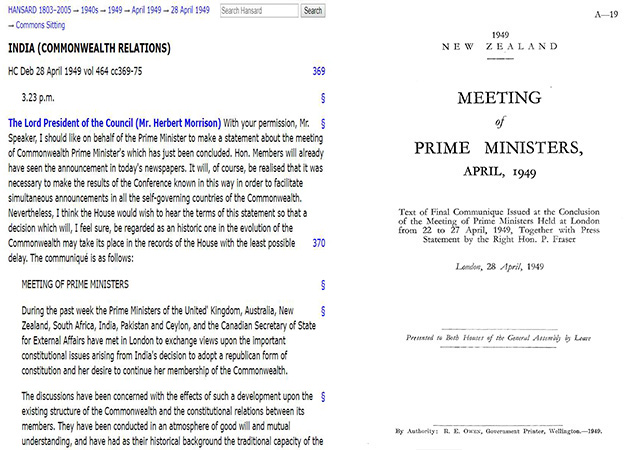

This year will see celebrations of ‘Commonwealth@70’ – the seventieth anniversary of the London Declaration of 28 April 1949, which, according to the Commonwealth Secretariat, but also, for instance, Wikipedia, marked the ‘birth of the modern Commonwealth’.

The declaration came about because India wanted to become a republic but also stay in the Commonwealth (unlike Ireland which, days before, had left). Previously, member states were united by a supposed common allegiance to the crown. In the end, the formula was adopted:

‘The Government of India have … declared and affirmed India’s desire to continue her full membership of the Commonwealth of Nations and her acceptance of the King as the symbol of the free association of its independent member nations and as such the Head of the Commonwealth’.

Despite doubts particularly from Australia and New Zealand – and the wry complaints of King George VI at being reduced to an ‘as such’ – the formula enabled India to remain in the Commonwealth.

How did the Round Table see it at the time?

Surprisingly perhaps, the Round Table saw the declaration as effectively ‘little change’:

‘The declaration…has surmounted a great crisis in the constitutional development of the British Commonwealth by the practical, and indeed traditional, resource of saying in effect that no crisis exists ….the declaration has been rightly applauded…for it makes in the structure of the Commonwealth as a whole the least possible change compatible with India’s exercise of her undoubted right to renounce a system of symbolism which in her case could not serve its essential purpose’.

Smugly, the journal went on to quote Tennyson, on ‘our slowly grown/ And crowned republic’s crowning common sense/ That saved her many times’. This was largely the view of other commentators (a rare exception being the young Sonny Ramphal).

Why?

By 1949 many of the essentials of the Commonwealth were already in place. If Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings (CHOGMs) are central to the modern Commonwealth, the Commonwealth can perhaps date itself to 1887 (with the first ‘colonial’ conference; after several changes of name they became ‘CHOGMs’ only in 1971). India was represented at these meetings – albeit by appointed members – from 1917 on. 1919 saw the separate representation of India (as well as Canada, Australia, and the other ‘dominions’) at the League of Nations.

Vastly more significant was the 1931 Statute of Westminster, which declared Commonwealth states to be

‘autonomous Communities … equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs … and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations’.

Clearly, Commonwealth countries possessed complete self-government before 1949. This was emphatically illustrated by Ireland’s neutrality throughout the Second World War.

What did the declaration achieve?

The declaration achieved its primary aim, to keep India in the Commonwealth. It also settled the question (albeit ostensibly only in India’s case) of whether a republic could remain in the Commonwealth.

Did it end the role of the British monarchy in the Commonwealth? Absolutely not. Indeed, as Philip Murphy has described in his book on Monarchy and the End of Empire (2014), the declaration provided a new role for the monarchy, independent of the UK government. Ask anyone in Canada or Nigeria or Fiji what the Commonwealth is about, and they will invariably mention the Queen. This monarch-centrism was accentuated at the 2018 CHOGM.

Did it mark the end of the ‘British’ Commonwealth? Independent India had been represented at the 1948 prime ministers’ conference (alongside Pakistan and Ceylon). Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and especially Ireland and South Africa, had hardly been docile followers of the UK before then. On the other hand, prior to 1965 Commonwealth diplomacy was still coordinated through the UK’s Cabinet Office and Commonwealth Relations Office. Arguably, the Commonwealth was Anglocentric for much longer. In terms of image it remains so.

Did the declaration, at least, encourage other countries to join (or remain)? Pakistan and Ceylon would undoubtedly have remained, for the time being, had India left (indeed both countries initially argued against changing the rules in 1949). As for countries in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific, a Commonwealth with India in it did at least prevent the Commonwealth becoming a mere instrument of western Cold War policy. In terms of membership, though, the decisions to include Ghana (1957) and Cyprus (1960), in both cases after extensive discussion of two-tier status, were arguably more significant, opening the way to the inclusion of small states which now make up the majority of the Commonwealth.

So have we got the right anniversary?

Clearly there are many other claimants. 1931 perhaps leads the field – though celebrating its anniversary is complicated since Australia didn’t adopt it until 1942, and New Zealand until 1947. For the ‘modern’ Commonwealth, other dates hove into view: the enforced departure of South Africa in 1961, the first real example of Commonwealth values in action; 1965, for the founding of the Commonwealth Secretariat (in fact the Secretariat celebrated ‘Commonwealth@40’ in 2005, but memories are short); 1971, for the Singapore declaration; 1991, for the Harare declaration; perhaps even 2012, for the Commonwealth Charter.

In truth the Commonwealth has been stubbornly and quintessentially evolutionary, and it is difficult to pick out any one date for its ‘birth’. But if ‘Commonwealth@70’ is largely a myth, perhaps it is a useful one. More than any of the other dates, 1949 symbolises the birth of a ‘modern’ Commonwealth of diverse societies and cultures. It might not be too much to hope that it also comes to symbolise a Commonwealth which does not rely on inherited ties or the vestiges of monarchy to justify its existence.

Alex May is the Honorary Secretary of the Round Table Editorial Board.