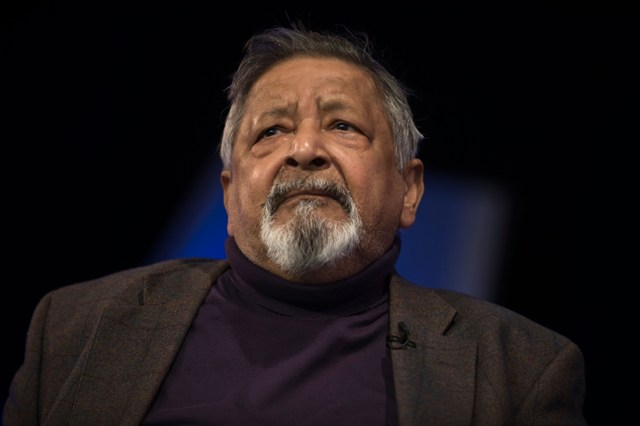

V.S. Naipaul Nobel Laureate author pictured at the Hay Festival 2011. [photo: Alamy]

V.S. Naipaul Nobel Laureate author pictured at the Hay Festival 2011. [photo: Alamy]

[This is an excerpt from an article in the current issue of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

Indeed, there is no person who has written more on Trinidad, for a longer period of time, to a wider audience than Naipaul. Even when he was writing about a place like Malaysia, he would centre himself by noting things like trees that he recognised from growing up in Trinidad. This is not someone who hates himself or his heritage. He wrote extremely affectionately, with great detail, precision, and care, but never flinching from the truth of his observations, as he saw them. Indeed, more than anything else, he hated people who lied to themselves and, worse, banked on others believing those lies.

He was often misunderstood. For instance, the famous line ‘nothing was created in the West Indies’ was not a criticism primarily about the former slaves and indentures. It was a criticism of the British. He wrote that line in 1960 when we were still colonies. How could it mean anything else? In Spanish America, the colonialists built substantial public buildings, plazas and great universities that still stand today. In colonial New England, the venerable institutions of Harvard and Yale were built. Under British colonialism in the West Indies, massive wealth was generated here for a time, but nothing was created.

From this background Naipaul had one obsessive concern: ‘How do I, as a Trinidad Indian, born in this small colony, isolated from the rest of the world, marginal even here, find my way in the world?’ It was the great theme of his life’s work. He developed many sub-themes and recurring characters from it, returning to them over and over again: the futility of people trying to run away from themselves, the fraudulence and danger of white liberals, the Trinidad ‘smart man’ and the more brutal manifestations of this character in other societies. In fact, it is as if Naipaul spent his life writing just one Big Book, with each new publication simply being an additional volume or chapter in it.

Many do not realise the importance that Trinidadian intellectuals Eric Williams (the renowned historian and country’s first prime minister) and C.L.R. James (all three of whom attended Trinidad’s Queen’s Royal College) had on this phase of Naipaul’s life. Naipaul himself attests to this. He credits James with making him realise the larger, universal themes and issues that were unconsciously underpinning A House for Mr. Biswas, and they corresponded. In 1960, Eric Williams – as premier of Trinidad and Tobago in the now forgotten Federation of the West Indies – invited Naipaul to travel the Caribbean and write his first book of non-fiction, which became The Middle Passage. Williams gave Naipaul use of his substantial personal library. On the other hand, Prime Minister A.N.R. Robinson later told Naipaul that it was because he read Among the Believers that he was able to understand and deal with the Jamaat-al-Muslimeen as he was held hostage during the failed 1990 coup.

Naipaul showed all of us what we can be on the world stage, even if we were born in its periphery. His advice to us was what his father gave to him when he left Trinidad: ‘Find your centre’. It is only then that we can find our way in the world.

Kirk Meighoo is a Political Analyst/Historian and a former Independent Senator, Trinidad and Tobago.