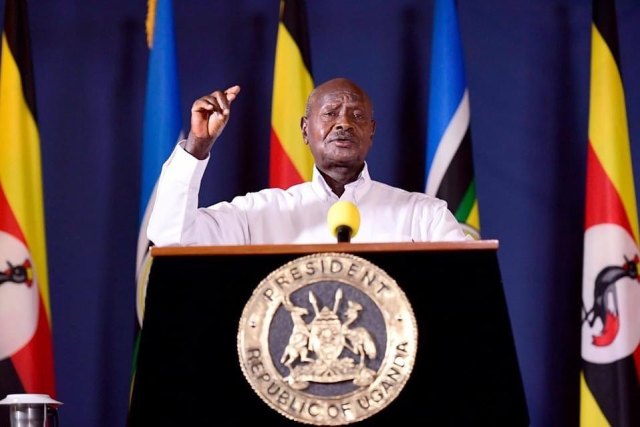

President Yoweri Museveni speaking in January 2021. [Photo: Government of the Republic of Uganda.]

President Yoweri Museveni speaking in January 2021. [Photo: Government of the Republic of Uganda.]

‘The problem of Africa in general, and Uganda in particular, is … leaders who want to overstay in power,’ the 40-year-old Yoweri Museveni declared at his swearing-in ceremony in 1986. Asked about this after the 2006 elections, as he entered his third decade as president, Museveni said he meant ‘longevity without democracy … dictatorship.’ But he hinted that he would not stand in 2011: ‘I will be quite an elderly man.’

Now 76 and beginning his sixth term in office (he first stood for election 10 years after seizing power), Museveni is now regarded by many, in the words of Nigeria’s Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, as ‘the very thing he fought against’. Officially, Museveni won the presidential election on 14 January with more than 6m votes, or 58.4%. His main opponent, Bobi Wine – stage name of the singer-turned-politician Robert Kyagulanyi, the self-styled ‘ghetto president’ – won 3.6m votes, or 35.1%. The ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party said Museveni’s victory proved that ‘opponents failed to offer any alternative apart from empty promises’.

However, Wine – who was immediately put under house arrest – blamed ‘fraud and violence’. His claim to have proof of vote-rigging was dismissed by Museveni’s lawyers, who said videos of police ticking ballot papers were forged. Uganda’s Observer noted 100% turnout at 409 polling stations, at which Museveni won 96% of votes. Questioned in parliament, Gen Jeje Odongo, internal affairs minister, admitted that 44 people had been ‘reported kidnapped’, with 31 still missing. MPs pointed out that the security agencies had carried out the abductions. In January, the police inspector-general, Martin Okoth Ochola, told the press: ‘We shall beat you for your own sake.’ Several journalists were taken to hospital after military police attacked them as Wine delivered a petition to the United Nations in Kampala.

The UN expressed concerns at the ‘deteriorating human rights situation’ and noted the deaths of 55 protesters after Wine’s arrest in November. The UN human rights office, the OHCHR, cited arbitrary arrest, harassment, detention and torture of opposition candidates and supporters. Human Rights Watch said the elections were marked by ‘widespread violence and human rights abuses’, including killings by security forces, arrests and beatings of opposition supporters and journalists, and disruption of opposition rallies. Amnesty International noted that police had fired at Wine’s car and condemned ‘persistent use of excessive force by the security forces, arbitrary arrests and detention, and attacks on journalists’. The Human Rights Network for Journalists–Uganda also reported widespread attacks, detentions and intimidation of the press.

Ugandans are familiar with this. In 2011, as Museveni’s former friend and doctor, Kizza Besigye, stood against him for a third time, the Guardian said the results ‘raise questions over the fairness of the election’. After running again in 2016, Besigye called it ‘the most fraudulent electoral process’. Commonwealth observers’ recommendations, such as reining in security forces and ensuring transparency in vote-counting, were ignored. Citing the risk from Covid-19, Uganda’s election commission banned rallies two weeks before the polls (the opposition claimed this only affected areas where Wine had not yet campaigned) and said electioneering should continue online. Facebook and Twitter then suspended accounts they linked to Uganda’s information ministry for undermining debate (such as identical messages backing a police crackdown on opposition supporters). Museveni accused Facebook of taking sides, saying: ‘Uganda is ours.’ A four-day internet and social media blackout was imposed. The internet freedom monitor Netblocks said the shutdown cost the Ugandan economy about $9bn. There were also questions about how election officials could declare the result without internet connections for 39,000 new biometric voter-verification machines. Juliet Nanfuka from CIPESA, a digital rights organisation, called it ‘a familiar electoral trend in Uganda’, citing social-media bans in 2006 and 2011. In 2016, as Besigye closed the gap in opinion polls, the government blocked access to Twitter, Facebook and Whatsapp. Museveni called it a ‘security measure to avert lies’. This year more than 100 virtual private networks, used to circumvent shutdowns, were also blocked.

Now with 61 seats, Wine’s National Unity Platform became the biggest opposition party but he filed a petition to overturn the results (Wine – an MP since 2017 – later withdrew the case, claiming judicial bias). The debate within the NUP over appealing to a judiciary it sees as compromised, and whether this endorsed Museveni’s win, points to an opposition split between those wanting to use the system to remove Museveni and those favouring street protests. This divide could weaken backing for Wine, who has been criticised by erstwhile followers for ideological naivety and by the NRM for relying on ethnically based support (the NUP is strongest in the central region that was once the Buganda kingdom).

Neither the US government nor the European Union congratulated Museveni on his victory. The EU said previous observer missions’ advice had been ignored. The US ambassador tweeted that the elections lacked ‘accountability, transparency and confidence’. Mindful of its position as the former colonial power (and of Uganda’s role fighting Somalia’s al-Shabab jihadists), the UK was less critical, merely noting ‘concerns about the overall political climate’. Patricia Scotland, Commonwealth secretary-general, appealed for free and fair elections, though the organisation appears to have kept silent publicly otherwise.

A Washington Post editorial said Museveni’s ‘regime has grown steadily more corrupt and autocratic’ and called him an ‘aging ruler [who] has evolved from reformer to tyrant’. In Foreign Policy, the Kenyan writer Carey Baraka called it a ‘grand electoral theft’ and suggested Museveni could no longer be removed through the ballot box. After seizing power by force – wearing military fatigues as he was sworn in – Museveni keeps the military at the heart of government. Moses Khisa calls it a ‘military dictatorship draped in civilian garb’. As well as Gen Odongo, the first deputy PM is Gen Moses Ali; Gen Elly Tumwine is security minister; and Gen Katumba Wamala is minister of works and transport. This clearly shapes policy, as seen in Tumwine’s remarks after protesters were killed in November: ‘Police have a right to shoot you.’ Wine’s wife said Uganda was now worse than under Idi Amin. Museveni may once have declared democracy to be ‘the right of the people of Africa’ and that governments were not ‘masters but the servers of the population’, but he also scrapped constitutional limits to presidential terms in 2005 and the age of the president in 2017.

Writing in Foreign Policy, Wine said: ‘The international community is part of our enduring problem … Museveni has managed to position himself as a military ally and development darling of many western governments that look the other way when it comes to his horrendous human rights record … Museveni also embraced neoliberal economic reforms that have been hard on the poor but endeared him to institutions such as the World Bank.’ But that may be changing. Washington condemned the ‘undermining of democracy and human rights … security force violence … and election irregularities.’ Brussels criticised ‘violence in the pre-electoral period, harassment of opposition leaders, suppression of civil society actors and media.’ Museveni has long dismissed such criticism, declaring in 2006: ‘If the international community has lost confidence in us, then that is a compliment because they are habitually wrong.’ Nevertheless, Museveni was ‘no longer a guarantee of Ugandan stability but increasingly represents a pathway to instability’, according to Alex Vines, at Chatham House.

It is unclear whether Wine can maintain pressure on Museveni. Addressing a seminar of London University’s Institute of Commonwealth Studies, he urged the Commonwealth ‘to call Museveni to order’ but gave no details of plans beyond declaring: ‘We are confident in the people of Uganda … to communicate their dissatisfaction with the dictatorship.’ Nevertheless, criticism is mounting outside Uganda. As well as condemning the violence and abuses reported by 3,000 observers deployed for the polls, the Africa Elections Watch coalition questioned the impartiality of Uganda’s supreme court and the African Union’s silence, and called on the international community to turn its disapproval into ‘measurable actions’. Writing in the New York Times, Murithi Mutiga, of the International Crisis Group, urged a boycott of elections without reforms such as an independent electoral commission, true freedom of assembly and limiting state campaign spending.

As the Observer noted, ‘decades of economic growth and subsidies have won Museveni a mass following in rural areas’ as poverty rates were halved. But Uganda has a young, impatient urban population (Uganda’s median age is just 15.7) with no memories of Museveni’s role in ending the Amin and Obote regimes’ abuses. According to Anders Sjögren, at Uppsala University, Museveni appeals to the public with ‘ideological and nationalistic posturing’, while ‘using money to win the support of insiders and buy off opposition’. Ultimately, however, he had ‘always looked on violence as a preferred option rather than a last resort’.

Without concerted pressure from abroad to support grassroots opposition in Uganda, as well as closing the taps on the vast military aid Museveni uses to keep his security forces onside, the situation is likely to get worse in Uganda before it gets better. As Soyinka warned: ‘Museveni’s going to fight to the end, and he’s going to continue to fight dirty because he believes power is his natural birthright.’