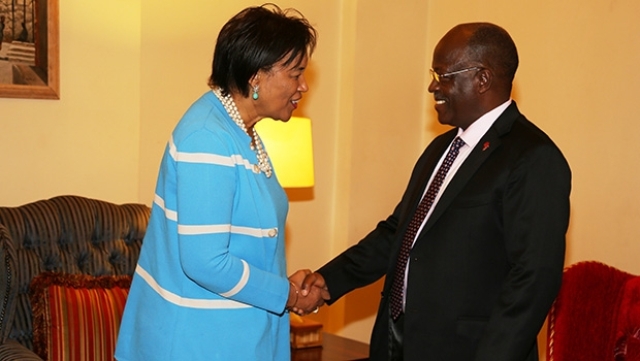

Commonwealth Secretary-General Baroness Patricia Scotland with Tanzanian President John Magufili in 2017. [photo: Commonwealth Secretariat]

Commonwealth Secretary-General Baroness Patricia Scotland with Tanzanian President John Magufili in 2017. [photo: Commonwealth Secretariat]

The Tanzanian president, John Magufuli, has died, aged 61. His vice-president, Samia Suluhu Hassan, announced on state television that he had died from heart failure in a Dar es Salaam hospital on 17 March. Hassan, as acting president, is the first woman to lead Tanzania and currently Africa’s only political, rather than ceremonial, female head of state.

Magufuli had not been seen in a fortnight, with rumours swirling that he was ill. Tundu Lissu, a leader of the opposition Chadema party, told the BBC before Magufuli’s death that the president was being treated for coronavirus in a Kenyan hospital, adding that this would not surprise Tanzanians. ‘He has never worn a mask, he has been going to mass public gatherings without taking any precautions,’ Lissu said from exile in Belgium. ‘This is someone who has repeatedly and publicly trashed established medicine.’

Reporting his death, the Guardian called Magufuli ‘one of Africa’s most prominent Covid-19 deniers’. It said senior officials had died from Covid but Magufuli had denied the disease was spreading and discouraged mention of it by health workers. Since May Tanzania has ignored the World Health Organization’s requests for details of the country’s caseload (officially just 509 among a population of 58 million), and has no testing or plans for vaccination.

Magufuli was cautious when the pandemic began but then declared that Tanzania was Covid-free, repeatedly denied that the disease had spread, claimed without evidence that vaccines were dangerous and told people instead to pray and inhale herbal-infused steam. He said in January: ‘Vaccines are not good. I don’t expect to announce any lockdown because our God is living and he will continue to protect Tanzanians.’

Born in 1959, and first a teacher and chemist, Magufuli was elected an MP for the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi party in 1995, becoming a deputy minister the same year. As minister for works and transport, he earned the nickname ‘the bulldozer’ for his attack on corruption in roadbuilding, and was elected president in 2015. ‘Magufuli came in on the platform of fighting corruption and empowering the masses,’ said Martin Adati, a Kenyan analyst.

His popular anti-corruption drive saw him purge the civil service and teaching staff of some 30,000 employees with fake qualifications but he soon showed an autocratic side by sacking an information minister who spoke up for press freedom and had a rapper arrested for a perceived slight in a song. The opposition politician Zitto Kabwe, leader of the ACT-Wazalendo party, declared that Magufuli was ‘sowing the seeds of a dictatorship’. After Magufuli was re-elected last October, amid claims of electoral fraud, restrictions on social media, arbitrary detention and police shootings, opposition politicians were rounded up by police or went into hiding. Many feared Magufuli planned to scrap the two-term limit for presidents.

Although he belatedly acknowledged how Covid-19 was devastating the country, admitting that the ‘respiratory disease’ had killed the head of the civil service and urging Tanzanians to wear masks, Magufuli’s proud legacy of fighting corruption was indelibly tarnished by his lethal refusal to accept the reality of Covid-19.