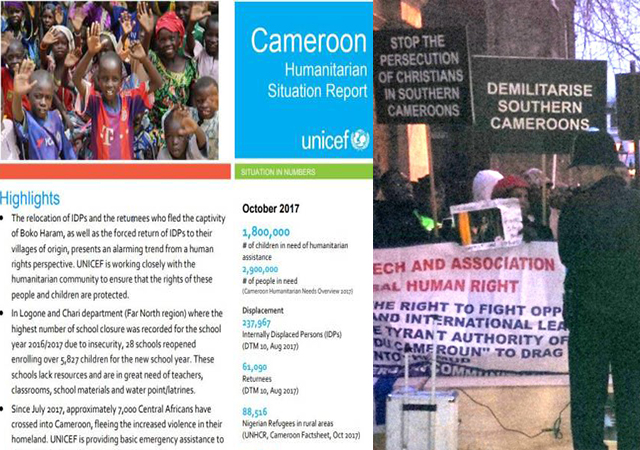

(l) UNICEF reports in 2017 on the growing Cameroon crisis and (r) Cameroon protesters outside the Commonwealth Secretariat on Commonwealth Day 2018. [UNICEF and Photo: Debbie Ransome]

(l) UNICEF reports in 2017 on the growing Cameroon crisis and (r) Cameroon protesters outside the Commonwealth Secretariat on Commonwealth Day 2018. [UNICEF and Photo: Debbie Ransome]

Thousands of Cameroonians have fled to Nigeria after violence flared in the anglophone provinces of North-west and South-west Cameroon. The exodus was sparked by Cameroon’s security forces firing on protesters in the increasingly restless region, killing 40 and injuring 100, the Guardian reported. A mayor said one victim was a 13-year-old girl. Hundreds of the English-speaking minority (about 20% of Cameroon’s population) were imprisoned, ‘packed like sardines’ according to Amnesty International.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees said it was stepping up its presence in Nigeria’s Cross River state to support 7,200 arrivals, with thousands more awaiting registration as asylum seekers. Earlier, the UN refugee agency warned that 40,000 people may flee to Nigeria, although that ‘might actually be a conservative figure’. The region is already devastated by the Boko Haram insurgency, which has displaced about 2.5 million people in Cameroon, Chad, Nigeria and Niger.

On the day of the protests, the Southern Cameroonian United Front movement symbolically declared independence for the proto-state of ‘Ambazonia’ (following an earlier UDI in 2006). As reprisals followed, eight Cameroonian soldiers were killed by suspected separatists in November. ‘A secessionist push in Cameroon’s English-speaking regions is on the brink of a full-blown revolt,’ said Bloomberg. The International Crisis Group (ICG) warned: ‘The anglophone crisis calls the foundations of the Cameroonian state into question.’ Cameroon Intelligence Report declared: ‘Ambazonia has come to stay…the Southern Cameroons crisis is slowly but surely turning into a guerrilla war.’

A year of steadily increasing tension began with a strike by English-speaking lawyers, teachers and students against francophones’ appointment to courts and schools in the region. It was the greatest threat yet to the rule of Paul Biya, Cameroon’s president for 35 years, said Reuters. His forces responded brutally, with at least nine people killed, then internet access was cut off in the anglophone region in January 2017. The UN’s special rapporteur for human rights said: ‘A network shutdown of this scale violates international law.’ In September, as Biya addressed the UN General Assembly in New York, anglophone Cameroonians marched in their thousands. The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative warned of the worsening situation, urging the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group to demand the release of political prisoners, investigation of illegal detention, ‘disappearances’ and torture, and meaningful dialogue on language rights. It also noted a radio station and newspapers being shut down and arrests of journalists (such as RFI’s Ahmed Abba, who served nearly three years of a 10-year sentence).

For Ambazonia’s ‘foreign minister’, Amos Mudoh, it was all about the oil. He told Sputnik. ‘Paul Biya is a stooge of France. He is a governor, not a president. Cameroon is a colony … Cameroon makes $10m a day from crude oil from Ambazonia. But we don’t even have schools. The oil money is siphoned off to French Cameroon.’ Mudoh had a point: offshore energy reserves are the mainstay of the economy, with oil and gas generating nearly half of foreign exchange and a fifth of government revenue. Oil was discovered in 1955 and the French giant Total dominated Cameroon’s energy sector after independence, selling its concessions to another French company, Perenco, in 2010. But the steep fall in oil prices and shrinking reserves hit Cameroon badly, forcing it to go to the International Monetary Fund for a $666m line of credit last year. As population growth accelerated, the number in poverty jumped 12% to 8.1 million people in 2007-14, the World Bank said.

Meanwhile, Nigeria is becoming ever more drawn into Cameroon’s conflict after the ‘Ambazonians’ said their leader, Sisiku Julius Ayuk Tabe, and six others were abducted by Cameroon ‘gunmen’ in Abuja. The BBC said the separatists had been arrested by Nigeria’s intelligence agency, the Department for State Service, although this was officially denied. A Nigerian human rights lawyer, Femi Falana, called for the seven to be released, Nigeria’s Daily Post reported. He said their detention was illegal and southern Cameroonians had a right to self-determination. But Biya, who faces re-election this year (though his wins so far have all been formalities), seeks a military solution to the separatist issue. ‘Large-scale army operations are being prepared’, a security source told AFP. ‘The authorities have already imposed night-time curfews, restrictions on movement, raids and body searches.’

Biya will need to undo decades of English-speakers being marginalised and disempowered to bridge the gulf between his administration and the anglophone community in Cameroon. The separatist movement’s origins lie in the messy, unresolved aftermath of the country’s independence from France in 1960 after the UK opposed independence for its mandate territory of German Cameroun. Divisions among anglophone parties led the Muslim-majority Northern Cameroons to join Nigeria while Southern Cameroons joined the former French mandate territory on severely unequal terms. That imbalance became entrenched under the centralising, anti-federalist tendencies of Biya and his predecessor, Ahmadou Ahidjo, with broken promises and repression hardening attitudes and eroding the chances of a federalist solution to the push for separatism. ‘The ongoing crisis is about decolonisation, not secession,’ says the Cameroonian journalist Eliza Anyangwe in the Guardian.

But now the winds of change are blowing through Cameroon. ‘Never before has tension around the anglophone issue been so acute,’ the ICG warned. ‘The majority of anglophones are far from happy. Having lived through three months with no internet, six months of general strikes and one school year lost, many are now demanding federalism or secession.’ Southern Cameroonians’ demands for independence no longer go unheard in the west, with calls for a UN-supervised independence referendum and for the Commonwealth to warn Biya that his country faces expulsion. The ICG also called for a stronger response from the international community to avoid the conflict threatening the stability of a country already fighting Boko Haram in the north and Central African Republic militias in the east. ‘It could begin by emphasising the right of anglophones to discuss their future and that of their country, to better political representation and to expect greater official willingness to take into account cultural and linguistic differences.’

Southern Cameroonians hoping for a robust condemnation of Biya’s crackdown by the Commonwealth were disappointed. ‘As the Commonwealth family, we will do everything we can to preserve the unity and peaceful existence of any member,’ the secretary-general, Patricia Scotland, said on a visit to Yaoundé. ‘I therefore encourage Cameroonians from all walks of life to embrace peace, unity and resolve any differences through peaceful dialogue.’ The Cameroon Concord said: ‘If all that Patricia Scotland succeeds to do about Cameroon is shake Biya’s bloody hand and mouth diplomatic niceties, she will go down in history as the Neville Chamberlain of Africa.’

There was equally fierce criticism of the Commonwealth’s response on social media: ‘The world is collapsing because organizations like the Commonwealth have become empty vessels,’ @AwahLivingstone said on Twitter. ‘Over 200 people have been killed in Cameroon in one year. Curiously, the Commonwealth can only make vague statements like “call for dialogue”.’ Another tweeter, @kisife, said: ‘The Commonwealth needs to step [up] her role of ensuring the respect of her values by member states. Otherwise, the Commonwealth is losing its value’. For @liquids25, the Commonwealth’s silence was ‘deafening, if not treacherous.’