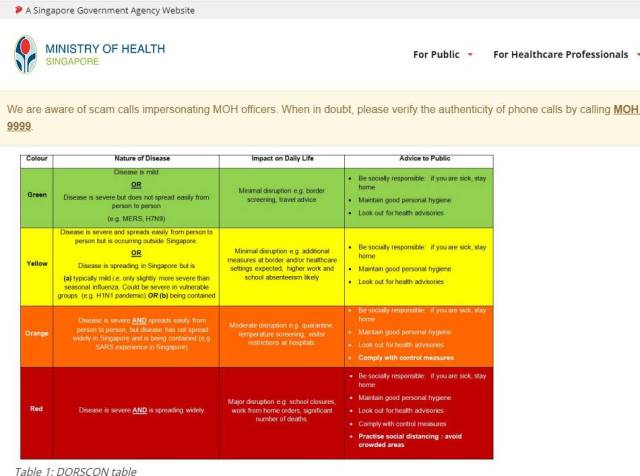

Singapore's Health Ministry provides a national Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) table online for the public and for health professionals.

Singapore's Health Ministry provides a national Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) table online for the public and for health professionals.

[This is an excerpt from an article appearing in the latest edition of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs. Opinion articles do not reflect the position of the Round Table Editorial Board.]

As the world is reeling from the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic that began in Wuhan, China in December 2019, Singapore, a developed Southeast Asian city-state of 5.8 million, was hailed, in the early days of the crisis, by public health experts and international media outlets as being at the forefront of response efforts.

Singapore has several characteristics that make it particularly susceptible to a pandemic and its impacts. It is small, densely populated and highly urbanised. It is also a major node in global finance, trade, and tourism with virtually no natural resources and a heavy reliance on imports. Recognising this, the Singapore government paid keen attention to Covid-19, taking notes on spread, outbreak control and management measures, and socio-economic impacts, particularly across China, Japan, Hong Kong, and South Korea. Singapore was also profoundly affected by SARS in 2002–2003, which served as a major driver of investment in health system and pandemic preparedness resources and infrastructure and the cultivation of local expertise in infectious diseases.

Informed by this knowledge, Singapore’s government moved quickly to implement control measures in direct response to the evolving local landscape. Temperature screenings for incoming flights from China were instituted in early January 2020, before Singapore’s first case was confirmed on 23 January. At the end of January, a multi-ministry taskforce was established to lead the Covid-19 response. Local transmission was confirmed on 4 February; three days later, the national Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) level was elevated from yellow to orange, signalling to the public that disease was severe and spreading, but was being contained. By March, Singapore had banned all entering or transiting short-term visitors and mandated a 14-day stay-home notice on those returning from abroad. These measures occurred alongside proactive public health initiatives including efficient and rapid testing, contact tracing, identification of clusters, quarantining of close contacts of confirmed cases, and mobilisation of primary care providers as first point of care for suspected cases.

Singapore has taken a stepwise approach to implementing social and physical distancing, introducing progressively stricter measures between February and March as the outbreak developed. These were supplemented by heavy penalties for defying quarantine and isolation orders and countering misinformation with constant communication from the government via press conferences, ministerial speeches, and messaging platforms like WhatsApp. As such, it came as no surprise to the public when Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced a month-long ‘circuit breaker’ from 7 April, which included closures of all non-essential workplaces and schools and prohibitions on all public and private social gatherings. Mask-wearing has been gradually implemented, with the government distributing reusable cloth masks to households and making it mandatory to wear masks outside people’s homes.

Singapore has also sought to reassure the public that its economic needs will be taken care of during and after the pandemic. The government was quick to pledge to its citizens and long-term residents that the costs of testing and treatment would be covered for all Covid-19 cases and that daily financial compensation would be provided to those under mandatory isolation or quarantine.

Suan Ee Ong is with the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health at the National University of Singapore.