[UNHCR website detailing Afghan refugees in Pakistan]

[UNHCR website detailing Afghan refugees in Pakistan]

[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs and Policy Studies.]

The Afghan refugees

The first major influx of Afghan refugees into Pakistan started in the late 1970s. During the Afghan-Soviet War, three to five million refugees came to Pakistan (Z. S. Ahmed, Citation2019). Since then, millions of Afghan refugees have remained in Pakistan due to political instability in Afghanistan. In 2019, Amnesty International reported 1.5 million Afghan refugees in Pakistan (Amnesty International, Citation2022). While Pakistan warmly hosted Afghan refugees for a very long time, the dynamics changed following the 2014 terrorist attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar in which 140 students were killed. This attack was carried out by the TTP and Pakistan blamed Afghanistan for letting this happen as, at that point, the TTP was mainly operating from Afghanistan (Boone, Citation2015).

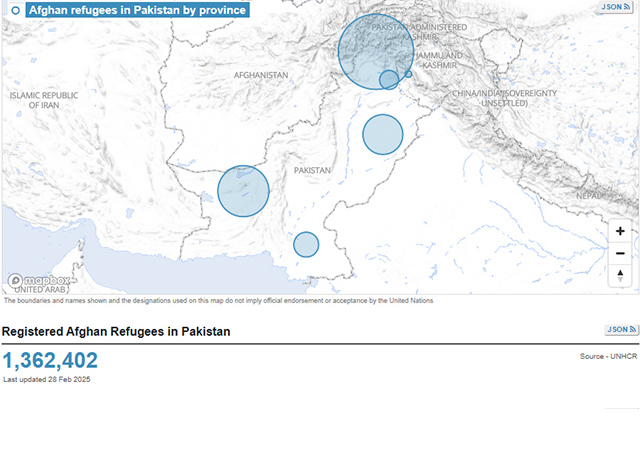

Pakistan’s policy on Afghan refugees has changed significantly since the 2014 Army Public School attack in Peshawar. Before this atrocity, despite not being a signatory to the 1951 Refugees Convention, Afghan refugees freely lived in Pakistan. After the attack, there was a crack-down and 365,000 refugees were forcibly returned to Afghanistan in 2016 (Z. S. Ahmed, Citation2018). Pakistan collaborated with the International Migration Organization to register un-registered Afghan refugees, and this process led to 879,198 new refugee registrations between 2017 and 2019 (IOM, Citation2019). Since the Taliban’s takeover, thousands more want to flee the country but there are now increasing restrictions from the Pakistan side. UNHCR data shows that the ongoing Afghan refugee flows are higher in KP and Balochistan as compared to other provinces (UNHCR, Citation2024). This is because of the proximity of the border regions and because of kinship relations (K. M. Shah, Citation2017). Hence, more than 80% of the Afghan refugees are living in the two provinces. This has been the case since the late 1970s as Afghan refugees prefer to live in KP and Balochistan and where they are operating a variety of businesses (Ahmadzai, Citation2016). As Table 3 shows, there has been a decline in Afghan refugees coming to Pakistan since August 2021. This is due to multiple reasons, including strict border management from the Pakistan side, such as the border fence, and now all Afghan citizens are required to obtain a visa before entering Pakistan (Sediqi & Yousafzai, Citation2021). The visa process is also slow because of an ever-growing number of visa applications received by Pakistan’s embassy in Kabul (Gupta, Citation2021). Since February 2022, there have been increasing problems along the Durand Line and occasionally there have been clashes between Afghan and Pakistan border security troops. In December 2022, an incident occured near the Chaman-Spin Boldak border crossing in which one person was killed and many civilians were wounded (Yousafzai, Citation2022). As bilateral relations between Islamabad and Kabul are deteriorating, there are more restrictions on Afghans entering Pakistan. By June 2023, the UNHCR reported that 1.33 million Afghan refugees were residing in Pakistan. The majority (52.6%) were living in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, followed by 24.1% in Balochistan.

Afghanistan: is the role of Pakistan’s intelligence apparatus overstated?

Pakistan at 75 special edition of the Round Table Journal

Conclusion

Owing to state fragility in Afghanistan and Pakistan’s border regions, particularly Balochistan and ex-FATA, residents have been both victims and perpetrators of transnational crimes and cross-border criminal activities. The Afghanistan-Pakistan border faces many challenges, including terrorism and drug trafficking. Border regions between the two countries present a somewhat similar dynamic to that in West African borderlands in terms of crime and instability. The security situation in KP, including ex-FATA, and Balochistan is particularly dependent on Afghanistan. This was also the case during the first Taliban regime, when Pakistan’s tribal belt received many Afghan refugees, and drug trafficking had also increased. Now, the border regions, particularly ex-FATA, are facing terrorism. A prominent anti-Pakistan terrorist group, the TTP, continues to operate from Afghanistan and has increased the intensity of its attacks since the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021. The state of Pakistan has not managed to fully implement its writ in ex-FATA, where governance reforms have been ongoing since its merger with KP, and Balochistan due to the presence of several non-state actors who have strong linkages with groups in Afghanistan. The Taliban’s inaction on Pakistan’s TTP-related concerns has further strained Afghanistan-Pakistan relations. Since August 2021, rising terrorism and drug smuggling have intensified instability in Pakistan’s border regions, posing a threat to both national and regional security in South Asia. Given the current difficult relationship between the two governments, this deeply problematic situation looks likely to continue.

Ilam Khana Riphah is with the Institute of Public Policy, Riphah International University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Zahid Shahab Ahmed is with the National Defence College, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates;c Alfred Deakin Institute, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia.