[montage of reports by Debbie Ransome]

[montage of reports by Debbie Ransome]

[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs and Policy Studies.]

Online harassment

One of the main digital threats against journalists is the online harassment that they face for the work that they undertake (Dodds et al. Citation2024). The reason behind the rise in online harassment is threefold, according to Waisbord (Citation2020) who notes that it is because of ‘easy public access to journalists, the presence of toxic internet right-wing far-right cultures, and populist demonisation of the mainstream press’ (p. 1037).

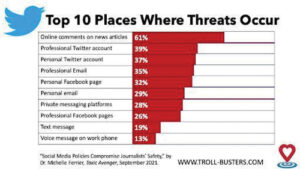

While social media tools like Twitter (now X), Facebook and Instagram have been one of the primary vectors of digital attacks, technological harms can manifest in a variety of ways. According to research by TrollBusters (www.troll-busters.com) and Ferrier (Citation2021), online threats tend to occur most in the online comment sections on news articles (61%), followed by professional Twitter (X) accounts (39%), then personal Twitter (X) accounts (37%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. TrollBusters top 10 places where threats occur.

Online harassment is also multi-faceted, including not only name-calling on social media, but cyberstalking, doxing, trolling, sending physical threats and, in some cases, online harassment can lead to offline harassment (Lenhart et al., Citation2016; Posetti et al., Citation2020).

- Impersonation: Occurs when a perpetrator impersonates someone (Beran & Li, Citation2005).

- Doxing: Occurs when one’s personal information – such as an address or phone number – is posted online (Gibb & Devereux, Citation2016).

- Exclusion: Occurs when a perpetrator purposefully excludes one from an online group, like a private forum (Beran & Li, Citation2005).

- Threat: Occurs when a perpetrator explicitly or implicitly threatens someone (Duggan, Citation2017).

- Technical attack: Occurs when a perpetrator interrupts one’s ability to access or manage their online presence, like hacking an email account or preventing a website from being accessed (Gibb & Devereux, Citation2016).

- Trolling: Occurs when a perpetrator seeks to elicit anger, annoyance or other negative emotions, often by posting inflammatory messages (Phillips, Citation2016). Trolling may include but is not limited to: (Mantilla, Citation2015)

- Concern trolling: Occurs when a troll pretends to share the opinions and ideas of others in order to increase conflict.

- Flaming: Occurs when a person verbally attacks someone.

- Raiding: Occurs when multiple perpetrators coordinate attacks on an individual.

- In person trolling: Occurs when harassment also takes place offline and may include calling someone’s phone or sending a SWAT team to their house.

- Gender trolling: When a troll intends to silence a woman or women through the use of gendered and sexualised language and threats (Mantilla, Citation2015).

In particular, for women journalists, the threats can also include sexual harassment, body shaming, racism and misogyny (M. Ferrier & Garud-Patkar, Citation2018; Pain & Chen, Citation2018; Posetti & Shabbir, Citation2022; Daniels and Douglas, Citation2025). In many instances, we see online harassment go unreported and journalists engage in avoidance or self-censorship as a coping strategy, or they might feel that they have to take leaves of absence (M. P. Ferrier, Citation2018; Stahel and Schoen, Citation2019; Makwambeni and Makwambeni, Citation2024; Ransome, Citation2024; Shah et al., Citation2024). In some cases, patriarchal societies make it difficult for journalists to report online harassment, particularly for women who feel that they have to be ‘strong like men’ as journalism is often a male-dominated industry (Chen et al. Citation2018; Koirala, Citation2020; Claesson, Citation2022).

From ‘Climate Barbie’ to “freedom of abuse”: Women in the online spotlight

Time to stand firm – social media and challenges to reporting

The Commonwealth and Challenges to Media Freedom

For journalists working in the Global South, research has shown that they are more likely to suffer from online harassment than their Global North counterparts because of a lack of multi-level governance interventions and semi-authoritarian contexts in which they report (Makwambeni and Makwambeni, Citation2024). Online harassment has also increased because, as the digital sphere has developed, journalists have become more reliant on using social media in order to increase their reach, search for sources and promote their stories (Lewis et al., Citation2020). As a consequence of this, journalists are left more vulnerable to online attacks (Reporters Without Borders, Citation2018) and, indeed, newsrooms are often ill-equipped to help them when they suffer from online harassment (Chen et al., Citation2018; Claesson, Citation2022; Nelson, Citation2023).

Online attacks against journalists can also come from a number of sources, including their own colleagues and media owners (Jamil, Citation2020; Zviyita and Mare, Citation2023). In some instances, online harassment is perceived as ‘mob censorship’ which is defined as ‘bottom-up, citizen vigilantism aimed at disciplining journalism’ (Waisbord, Citation2020, p. 1031), and comes from citizens or other non-state actors on the internet who might be acting in response to comments made by those in positions of power (Fang, Citation2024; Ndlovu & Khupe, Citation2023; Tandoc et al., Citation2021).

The impact of online harassment can be multi-faceted. In many instances, it can cause depression, stress and anxiety (Shah et al., Citation2024). It can also lead to self-censorship in an effort for journalists to try and keep themselves safe (Jamil, Citation2020). However, this then has a chilling effect on freedom of expression (Lewis et al., Citation2020). Journalists may decide not to engage with audiences on social media or they may also limit access to their accounts (Zviyita and Mare, Citation2023; Wheatley, Citation2025). In other instances, journalists may feel that they have to leave their profession because the online harassment they experience has become so intense (Ferrier, Citation2021; M. P. Ferrier, Citation2018). In South Korea, for example, Lee and Park (Citation2024) noted that there is a correlation between women journalists and the level of online abuse they endure and their desire to leave the profession.

Digital shutdowns

In other instances, journalists and their organisations have found themselves subjected to digital shutdowns by states. For example, the world’s longest internet shutdown took place in the state of Jammu and Kashmir in India in an attempt by the Indian government to control the flow of information (Neyazi, Citation2024). Particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was found that the crisis, which brought with it a plethora of misinformation, also caused governments to push through restrictions to silence critical journalism (Kneuer et al., Citation2024; Papadopoulou & Maniou, Citation2021). In certain instances, states justify these digital shutdowns by saying that they provide the ability to control the spread of misinformation and disinformation; however, in some cases this is used as a particular excuse for the state to spread their own disinformation without any resistance (Bleyer-Simon, Citation2021; Shah, Citation2021). Digital shutdowns also provide states with the opportunity to push disinformation. For example, in Sudan there was a shutdown to cover up the Khartoum massacre on 3 June 2019. During this time, it allowed the state the opportunity to circulate state-sponsored disinformation campaigns (Bhatia et al., Citation2023). Indeed, this is a tactic that we have seen deployed in countries in the Global South, including India (Neyazi, Citation2024), Sudan (Bhatia et al., Citation2023) and also in Indonesia (Rahman & Tang, Citation2022). The United Nations Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression and opinion, Irene Khan noted in her 2024 report that online violence, threats, hacking and targeted digital surveillance of exiled journalists have surged over the past decade and that too often, exile fails to provide safety:

Hundreds of journalists who have fled their countries continue to face physical, digital and legal threats from their home governments, including assassination attempts, assault, abduction, as well as prosecution in absentia on trumped up charges and retaliation against family members back home. (Khan, Citation2024)

Michelle Barrett Ferrier, Media Innovation Collaboratory, Trollbusters, Tallahassee, Florida, USA, Gemma Horton School of Information, Journalism and Communication, University of Sheffield, UK and Purva P. Indulkar Media Innovation Collaboratory, TrollBusters, Mumbai, India.