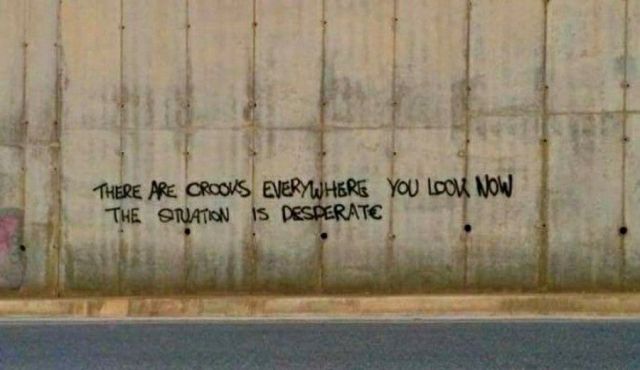

Quote from Daphne Caruana Galizia on a wall in Malta [picture: Daphne Caruana Galizia Facebook]

Quote from Daphne Caruana Galizia on a wall in Malta [picture: Daphne Caruana Galizia Facebook]

[This extract is taken from an opinion piece which appears in the latest edition of The Round Table: International Journal of Commonwealth Affairs.]

In April 2018, ahead of the Commonwealth summit in London, six Commonwealth organisations, including the Commonwealth-accredited associations representing journalists, lawyers and parliamentarians, together produced a carefully-crafted set of Commonwealth Principles on freedom of expression and the role of the media in good governance. At an event at the Senate House in London marking the publication of the text of the Principles, Desmond Browne QC for the Commonwealth Lawyers Association urged that it be adopted as ‘a universal code for the Commonwealth to protect freedom of expression and the activities of responsible journalists’. Yet despite warm words of encouragement spoken earlier by Secretary – General Patricia Scotland…and vigorous efforts to put the principles’ text on the summit agenda, nothing tangible came of it.

Why should it be different now? Because the crisis is real, and the Commonwealth is in the thick of it. A surge in the deaths of journalists in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan has made South Asia one of the world’s most dangerous regions for reporters. The gangland-style murder of Ghanaian investigative journalist Ahmed Hussein-Suale in January again demonstrated the risks to those who poke the hornets’ nests of secretive and corrupt power. Hussein-Suale led an undercover investigation that exposed high-level corruption in African football. He was shot dead near his home after a ruling party member of parliament called for him to be hanged and made public his home address.

Eighteen months after the car-bomb murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia, the most avidly read journalist in Malta, there are scant signs that Maltese authorities are close to finding and bringing to justice those who instigated or ordered the murder. This remains a crucial test case for the global fight against impunity. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Joseph Muscat has persisted in pursuing a libel case against Daphne by seeking damages from surviving members of her family, saying he would drop the case if they concede the original allegations were false. Her sons replied that they would not concede to ‘extortion’.

Such cases are part of an emerging global pattern of open governmental hostility to the work of journalists which the Commonwealth cannot afford to ignore: the rulers against the ‘watchdogs’. It is a short step from public officials venting their hostility in words to them misusing their power to act as the real enemies of press freedom. Whose side will the Commonwealth be on? In many member states lawsuits by public figures against the media, like photojournalist Shahidul Alam in Bangladesh, are commonplace. So are physical threats and closures of media organisations during elections.

Late last year the Secretariat invited back members of the six-organisation working group that co-authored the principles on media and good governance for a second try. The message was that fresh efforts to draw up a declaration or ‘charter’ on media and governance would be a priority. The work might even somehow be fast-tracked with a view to gaining the approval of Commonwealth leaders, perhaps as soon as at the next summit in Rwanda in 2020. The template, as outlined in the secretary-general’s oration in Westminster Abbey in October, would be a high-profile Commonwealth response to growing threats to journalists and other campaigners. She envisaged it as ‘augmenting existing commitment in the Latimer House Principles’.

Now for the hard part. Not just that next year’s summit will be held in Rwanda, whose government has a reputation for ruthless suppression of dissent. The heart of the matter is that protections for free expression and other rights cannot be merely rhetorical, but underpinned by effective safeguards and guarded by independent arbiters. The Commonwealth has to learn to listen genuinely to the voices of civil society and effect change. That would be a big leap indeed.

William Horsley is a member of the executive of the Commonwealth Journalists’ Association and the co-founder and international director of the Centre for Freedom of the Media (CFOM) at the University of Sheffield’s Department of Journalism.